Spoilers below.

Who is Ruth Handler? The Barbie movie doesn’t purport to know. By the time the biggest film of the summer cuts to its credits—riding the high of one last self-referential jab—the late Barbie creator’s background remains mostly unearthed; her tax scandal is batted away with a smirk; her ethereal presence manifests in a world neither dream nor waking. She is a strange sort of Charon on the River Styx of Barbie’s self-discovery. And as it turns out, Barbie’s “irrepressible thoughts of death” are much more nuanced than such a punchline might suggest, nor are they mere meme fodder from a particularly plugged-in marketing campaign. They’re the story of Barbie itself, and of Ruth’s role as a deified mother and mentor. With Ruth as guide, Barbie outgrows its box. Yes, friends, we finally know what Barbie is about: It’s a tale of death, and of what comes after.

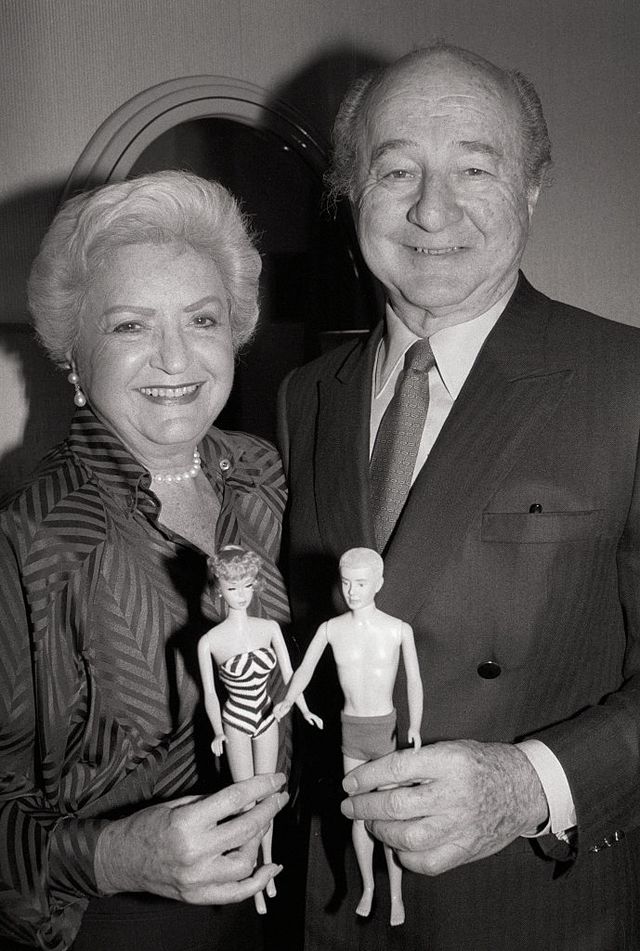

Deceased for more than two decades, Barbie’s Ruth is reincarnated in the body of actress Rhea Perlman, who plays the stout and grayed woman with a grit aching to escape its tiny enclosure. Born Ruth Marianna Mosko to Polish-Jewish parents in Denver, the Mattel co-founder designed Barbie as the first “adult” doll for children, a vessel into which they might pump their hopes and projections (and, ultimately, their insecurities.) The concept challenged the prevailing practice of girls and baby dolls; perhaps these kids didn’t want playthings that exclusively centered around motherhood, or games that mimicked the labor of their own parents. Barbie allowed them to envision not just a future for their children but for their own selves, grown and capable and—importantly—beautiful to behold. A doll with breasts? It was revolutionary.

More From ELLE

The idea sold, to a degree never since replicated. From 1945 to 1974, Ruth worked as president of the famous toy company, and Barbie—named after Ruth’s daughter, Barbara—grew into one of the most significant symbols of the 20th century. An eternal lighting rod for both women’s devotion and their feminist critique, Barbie has since sold more than a billion plastic figurines, even with encroaching competition from Bratz and Polly Pockets and My Scene and dozens of others eager to capitalize on the paradoxical aspirations and fears of American youth. No one could impede the force of those arched feet or that impossible waistline. In such a market, girlhood is a particularly salient structure, ubiquitous but malleable—and all too often fed to the whims of capital-driven influence.

It is in this murky reality that Barbie the film immerses itself, willingly, imperfectly, and with Ruth as an avatar. Perlman’s Ruth first appears midway through the movie, ensconced in the butter-yellow glow of a 1950s-style kitchen set deep within the fictional Mattel Headquarters. It is not immediately clear whether she’s being held there against her will, if she is a figment of Barbie’s imagination, or if Mattel itself has somehow mastered cryopreservation and reawakened her once-breathing body. The specifics don’t really matter (even if they’re fun to tease out). Margot Robbie’s Stereotypical Barbie stumbles upon Ruth by accident, as the former pursues an escape from the Mattel suits gunning to box her back up. Ruth seems unsurprised to find her own creation confronting her, and the two sip (or slurp) tea as Barbie laments the confusing prospects of the real world. In such a space, who is she, really? Is the feminism she thought she knew...totally fake?

Barbie doesn’t give Ruth much time to address that question—with Robbie’s character on the run—but Perlman reappears at the end of the film, suddenly and mysteriously manifesting in Barbie Land. As she and Stereotypical Barbie stroll together into a milky-white room with undefined borders (oddly reminiscent of the Harry-Dumbledore King’s Cross Station scene in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2, itself reminiscent of other depictions of the highway between death and afterlife), Ruth reveals herself as Barbie’s creator, and presents her with the Pinocchio proposition: either remain in her Dreamhouse forever, or become a real girl in the real world.

At this point in the film, Barbie has undergone a dramatic awakening. She can no longer operate in the headspace of “every day is the best day ever,” because she has witnessed the artificiality of such an idea, and the way in which it’s used as a tool of subjugation. She yearns for the power of choice, because it allows her to inhabit more than just one identity.

But Ruth makes the choice clear, in no uncertain terms: “Humans have only one ending. Ideas live forever.” If Barbie is to become human, she will exhibit the hallmarks of humanity: She will age. She will die. She will navigate the full range of human experience, as Ruth illustrates for her in a series of found-footage vignettes, depicting girls and their mothers in wondrous portraits of Americana. There is joy to be found in these sepia tones. But there is also darkness, a reality human Barbie will no longer be able to ignore. For hers was always ignorance, not genuine bliss; Barbie Land was never a true Eden, as Ryan Gosling’s Ken proves in his attempts to subvert the alternate dimension’s status quo. Now that Barbie’s aware of these contradictions, she must confront them. A weeping, gracious Robbie accepts Ruth’s offer with a whisper: “Yes.”

Here, Ruth operates as a fascinating guide to death, a keys-keeper at the door to the next chapter. She herself is deeply flawed: As the movie teases, Ruth resigned from Mattel in 1974 and was charged with tax fraud and false reporting in 1978, resulting in a $57,000 fine and 2,500 hours of community service. She died in 2002 after complications from a surgery for colon cancer. And, of course, she invented one of the most controversial icons of femininity in all of American history.

It is a testament to director Greta Gerwig’s creativity that Barbie’s “irrepressible thoughts of death” at the beginning of the film are more than just a ridiculous utterance from the lips of a plastic allegory. They’re foreshadowing for a bet Barbie ultimately makes, that the loss of an identity is sometimes necessary, and that it’s only terrifying if it’s the only one in our possession. Death is only the end if no other story exists. Ruth’s presence in the film, then, is almost Biblical, washed clean of her sins but all the more powerful for her awareness of them. Barbie acknowledges both the reality of death and the staying power of creative legacy. Ruth (and, in the context of the film, Barbie herself) passes on. Her story—and the questions it presents—are what we’re left to wrestle with.

Lauren Puckett-Pope is a staff culture writer at ELLE, where she primarily covers film, television and books. She was previously an associate editor at ELLE.