I’m obsessed with birth stories, but for so common an act, they’re hard to come by, which is telling in and of itself. For the last decade, I’ve asked people about their pregnancies, childbirths, and transitions to motherhood. The first birth story I heard was from a friend who was too afraid to learn anything about birth. She complied with her doctor’s orders during labor, but she tore badly while pushing, which she couldn’t feel because she was anesthetized. I hurt for her, and her experience haunted me. But I was certain that it was unique to her. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

The details variegate, but the takeaway is very often the same: birth didn’t go as planned; it went haywire. Healthy people with normal pregnancies become patients with risks, diagnoses, near-death experiences, damage. They assume—or are told after the fact—that something was wrong with their body or their baby.

Was the fact that I was hearing too many bad birth stories to count somehow a product of the people who gave birth? After all, in many cases, they reported to me that it was somehow their own fault.

Or did the blame lie elsewhere? At the feet of an overburdened hospital systems pushing profits or the patriarchal and white supremacist structures that created and govern them? To what extent did women and birthers believed these forces shaped their births and pregnancies.

In our society, we buy expecting mothers baby gifts. We notice, comment on, and touch their changing bodies. We mostly ignore and fail to support their shifting selves. Baby arrives, and she’s all we see. As if a literal stork dropped her off. The journey of the soul and body that gave birth aren’t discussed. Most often, they’re erased. Pregnancy turns our bodies into a new kind of public commodity and a receptacle for others’ ideas about who we are.

Women enter pregnancy brimming with all they have learned from books, films, the internet, and experts. We bring into the labor ward the stories we've heard, coveted, or wished away. My greatest fear was surgical birth or tearing. I expended so much energy during my first pregnancy praying to avoid those things. Many of us experience birth as disappointment, manipulation, and (whether or not we use this word) abuse. Sometimes we feel this as it’s happening; other times it goes unchecked, and we may need years to see it, if we ever do. We quietly blame a doctor who withheld support, a grouchy nurse, a problem with our body or baby that we internalize. Then we chastise ourselves for not having predicted or fixed it. We excuse bad judgments, unnecessary medicine we are “consented to,” horrendous bedside manner, or lies that masquerade as care. And we are gaslit into believing all of this is lifesaving—for our baby, for ourselves.

We slough off that birth attendants refused to do what we asked or failed to ask us before doing things to our bodies. We turn the blame inward when elements of our births don’t go to plan. If only we hadn’t hoped for that natural birth so hard. Stupid to enter an orchard wishing for magic fruit. Or perhaps we should have learned more about C-sections in birth class—we could have avoided surgery or prepared for it. We vow not to plan so hard next time, not to get our hopes up, lest we be disappointed and feel blamed again. We accept the mantra that birth is unpredictable and that we’re lucky, blessed, to leave with our lives intact and babies pulsing in our arms.

We don’t live in birth long enough to see it for what it really is. Birth is a system built in tandem with a profession founded on fear of the generative power of the birthing body. Obstetrics is a specialty constructed with the belief that Black pregnant bodies tolerate more pain and are predisposed to disease, while white pregnant bodies’ frailty requires expert control—medical arts, tools, drugs. The profession is highly skilled while simultaneously hamstrung by hospital systems for which maternity services turn the heftiest profit. Every birth is a manufactured healthcare crisis only doctors with rigid protocols in multi-million-dollar hospital systems can solve. It is a system that has evolved to control women for money.

Hospitals are where about 98 percent of American childbirth occurs. We go to them for many reasons—among them, culture and convention, the law, and ignorance. We flee the safety and security of our homes and the people we love and trust most and yield our bodies to facilities that exist to stave off death and treat disease. We easily accept the idea that they are safe places to birth because their function is preservation.

But we are in female bodies, Black bodies, trans bodies, and our protection is not guaranteed. In the hospital, our well-being and sometimes our lives are needlessly put at risk. A bevy of technologies, policies, drugs, practitioners, and administrators control us. They tell us that we’re too fast, too slow, too early, too late, too loud, too quiet, too much, not enough. These are familiar criticisms because, as women and birthing people, we hear them throughout our lives in other contexts. We come to know these condemnations like lovers. They first enter our thoughts and self-talk; then they worm into us, becoming not external modifiers but facts.

The truth is that no matter how much we learn about birth before having a baby, control is wrested from us with a sinister precision when birth day comes. We are told explicitly and implicitly that we are not experts in our own bodies, that strangers know best, that to be kept safe amid a tsunami of danger, we must submit to nameless faces who command with degrees, acronyms, mandatory procedures, protocols, monitoring, and an endless parade of fears. Physiological birth becomes not about nature, selfhood, or exaltation but about survival. And if you survive, well, even brutal means justify the end.

Reproduction and birth are about power—who has it and who doesn’t. The people doing the procreating don’t. Birth must return to our control. Our lives depend on it.

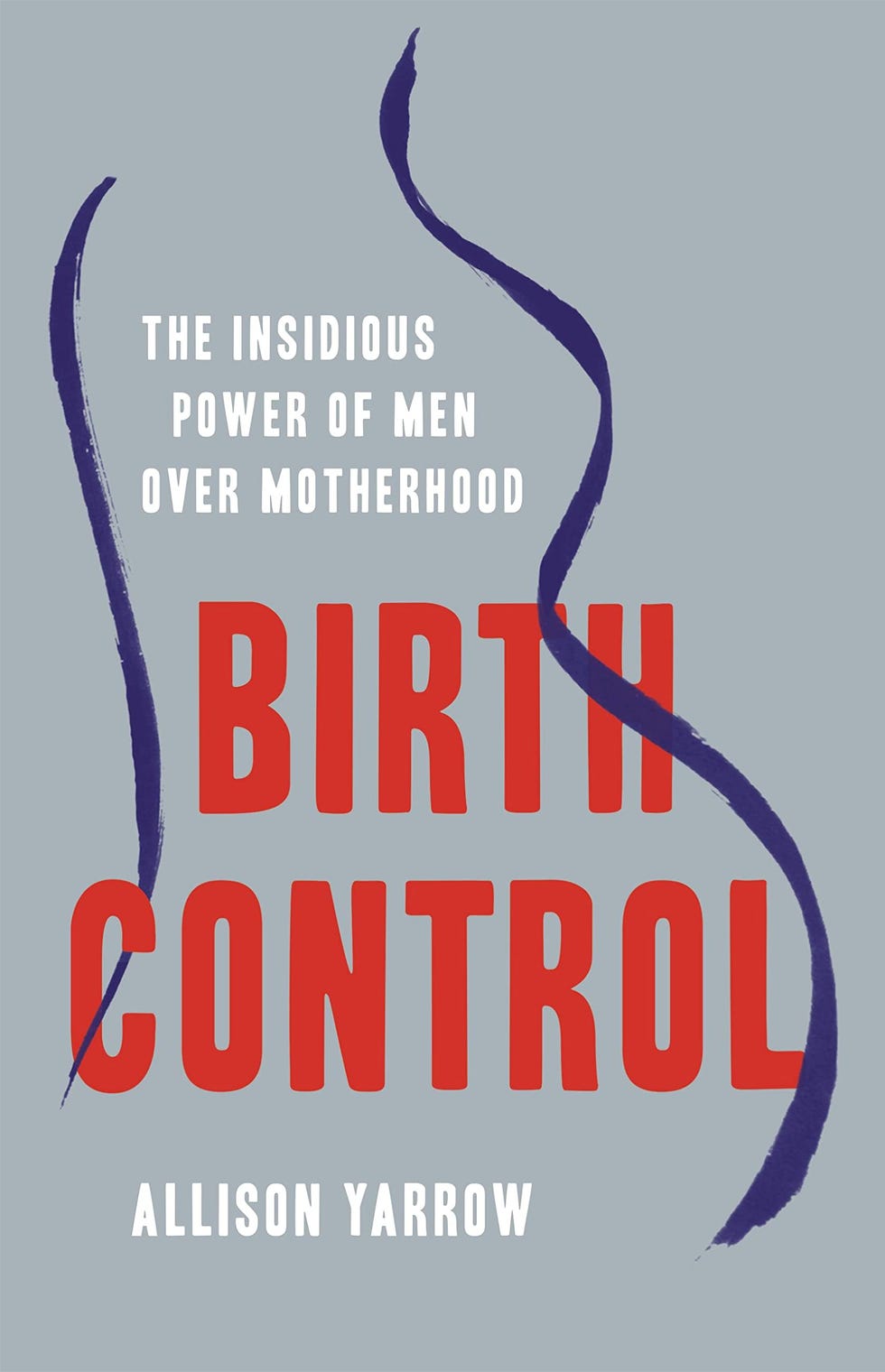

From Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men Over Motherhood by Allison Yarrow. Copyright © 2023 by Allison Yarrow. Published by Seal Press. All rights reserved.

Allison Yarrow is an award-winning journalist, speaker, and author of 90s Bitch, a finalist for the Los Angeles Press Club book award. She was a National Magazine Award Finalist, a TED resident, a producer at NBC News and Vice, a reporter and editor at Newsweek and The Daily Beast, and her writing and commentary have appeared in many publications.