On November 24, 2020, an alert popped up on my phone. Purdue Pharmaceuticals had pled guilty to federal criminal charges with an $8.3 billion settlement. The dollar amount seemed significant, but when I dug a bit further, I learned the Sackler family, who owns Purdue and has been accused of causing the opioid abuse crisis by marketing OxyContin as safe and nonaddictive, has so far escaped with no criminal charges. The vast majority of their wealth—as one of the world’s richest families—remains intact.

I have followed the Sacklers for years, tracking the lawsuits against them as mine suffered from opiate abuse. In 2017, I read “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain,” Patrick Radden Keefe’s longform piece in The New Yorker on the role the Sackler family played in addicting millions of Americans. Keefe lays out an unprecedented wave of criminal activity Purdue began in the early 1990s, using kickbacks and fraudulent marketing to saturate the market with its products.

Around the time Purdue's marketing campaign was picking up steam, a doctor wrote my mother a prescription for opioids. She has been addicted, on and off, ever since. I cannot prove it, but I strongly suspect the doctor who wrote my mother that prescription—and the subsequent doctors who renewed it or wrote new ones—were influenced by Purdue's corrupt, illegal marketing. Purdue's reach extended past the doctor’s office and the prescribing pad: To this day, my mother believes the lies Purdue told her doctors and repeats them as articles of faith.

As Keefe wrote, “Purdue officials discovered that doctors wrongly assumed that oxycodone was less potent than morphine,” a statement I often heard echoed back to me by my mother, who was terrified of morphine but willing to take its “safe” opioid relatives. Purdue insisted patients “who take OxyContin in accordance with its F.D.A.-approved labeling instructions will likely develop physical dependence,” but that dependence was not addiction. I’ve heard that from my mom, too.

My mother first kicked the habit in 1998, when I was 14. She replaced the pills with endless bags of Tootsie Roll pops and obsessive exercise. “You see, I don’t have an addictive personality,” she would say firmly. “I was physically dependent on narcotics and now I’m not.” Purdue was responsible for this canard—that only an intrinsically flawed person could abuse opiates—as well. In her 2019 filing against Purdue, Maura Healey, the Massachusetts Attorney General, cites a pamphlet Purdue distributed to physicians stating that addiction “is not caused by drugs” but “triggered in susceptible individuals by exposure to drugs.” Healey has spoken out against the DOJ’s recent settlement; her own state’s litigation is ongoing.

Even 22 years later, I remember how miraculous it felt when my mom got sober. I didn’t understand what was going on. All I knew was that a pall had lifted from our house. My mother stopped sleeping all the time; stopped vomiting bile into a plastic surgical bin at school pickup. Suddenly, she was more present—it no longer felt like she was always wrapped in cotton wool, always one layer removed from me. Not everything got better; my mother always has and always will struggle with mental illness and substance abuse. But right then? At age 14? I had my mom back.

Three years later, I wrote my college admissions essay about the Tootsie Roll pops and the sudden return of hope to our single-parent, Alabama apartment. I never thought about it as an essay about addiction. I didn’t understand why the teachers I showed it to cried and agreed to write me recommendation letters to wherever I liked. At the time, I didn’t even comprehend why I refused to let my mother read it. Child of a single mom who got clean makes good and goes to college. It’s a heartwarming story. But of course, things are rarely so simple.

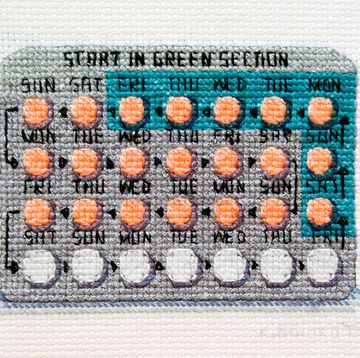

That essay got me a full ride to the Ivy League and a fighting chance to catapult myself out of the rural Alabama poverty my mother had run from her entire life. But the pills came back; they always came back. In college, it was Vicodin. On Christmas break my freshman year, my mom offered me one of her Vicodin for my migraines. At the time, I understood this as something a good mother would do: If a medication is truly safe and effective, why not share it? Yet in 2019, Russell Gasida, the former Sales VP of Purdue, testified that he told Richard Sackler via email that the sales team targeted patients “who had been taking low-dose Vicodin, Percocet, or Tramadol” as future consumers of OxyContin, according to the Massachusetts complaint.

Over the years, she would offer me her prescriptions to try frequently. When I had a migraine that wouldn’t break at 38 weeks pregnant, she insisted I should try a few Percocet. She repeated often that her doctors told her over-the-counter painkillers were far more dangerous than opiates. This sentiment, too, was part of the Sackler gospel.

When I was in grad school, she would keep her daily ration of Vicodin, Oxy, or Norco in a small porcelain case. We constructed an elaborate inside joke that she had a secret identity as “Porcelain,” a drug dealer. We were able to sustain this cognitive dissonance because my mother did not fit the picture of the “junkie” sold on Law & Order, shooting heroin and sleeping on the street. She had a pain problem: migraines, or maybe it was a brain tumor, or perhaps arthritis. It didn’t really matter which, because Purdue had succeeded in pushing the lie that Americans suffered from a plague of untreated, chronic pain to which opioids were the cure.

When I was six months pregnant with my first child at 27, she visited me in Paris. One night, she got into a physical altercation with a cab driver after accusing him of overcharging her (he didn’t). She wanted to call the police. Hours and a great deal of alcohol on top of the pills later, she screamed that I did not understand, that I was not supportive. She broke a wine carafe. When I stood up to leave, broken glass all over the hotel room, she told me I was endangering my baby by taking the metro in the early hours of the morning.

That was the first time I understood that it was my mom’s substance abuse that was the real danger. And that was the first time I tried to leave her: I wrote my mother a long letter explaining I wouldn’t remain in a space with her where she was abusing alcohol or combining alcohol with her pain medication. I stopped short of questioning her need for the opioids; even then, I believed they were harmless.

She told me she didn’t have a problem. Besides, she insisted, she could just fake a urine test and hire an actor to pretend to be her doctor, so I might as well take her on faith, or not at all. Love, I understood, required absolute faith and trust. About a year later, she had exploratory surgery for appendicitis symptoms and called me from the hospital, high on post-op opioids. “It’s strange, Tara,” my stepfather said in a call, “she was in terrible pain when she went in but when they took out her appendix, it looked fine.”

I went back, of course. I always went back. I told myself I had strong boundaries. I ignored when she showed up for visits with all the symptoms of withdrawal—a runny nose, shaky hands, mood swings. She simply had a lot of colds. I ignored when she insisted, in the Sackler gallery at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, that she’d never heard of OxyContin, before leaving a bottle of it on the kitchen table at my grandmother’s over Christmas. I refused to let her babysit after she nearly dropped my son as a baby, whiskey on her breath, but I let her see him.

The last conversation I had with my mother was Christmas Day, 2019. My grandmother had confided in me that my mother had tried rehab for the opioids when I was nine years old. I asked my mom about it, but she insisted my grandmother was lying, saying once again that she didn’t have a problem and begging me to swear I believed it too. “All of my prescriptions have been given under a doctor’s care, Tara,” she said, crying. “I am not an addict,” she insisted. Even then, I couldn’t tell her plainly that I thought she had a problem. “I would have been proud of you if you had gone to rehab when I was nine, Mom. I would have thought that was great. I love you,” I said. “But I didn’t go,” she said. “Please don’t put me in this position, Mom,” I answered, as calmly as I could.

When I wouldn’t swear to her innocence, she started yelling at my grandmother that she was a liar, that she was trying to steal Mom’s family from her. My son was standing there in the kitchen, confused. He was about to turn eight, about the age I had been when the pills started appearing in our Alabama apartment. And something in me snapped. “You will not do this in front of my children,” I screamed. “Get out,” I screamed.

I haven’t spoken to her since that day. I am coming to terms with the fact that I probably never will again. Not everyone gets their happy ending. But understanding that truth does little to mitigate my desire for justice. It is childish, perhaps, but I want the Sacklers to burn in hell, their names blotted out from history like failed kings of old. I’d settle for prison and the confiscation of every penny of blood money.

Not one member of the Sackler family has ever faced criminal charges for their role in opiate epidemic. Under the latest settlement with the Department of Justice, the Sacklers were not even required to testify under oath, protecting the full extent of their crimes from public view. The Trump Administration’s Justice Department charged no one—not one single person—with the felonies Purdue Pharmaceuticals committed. Corporations are not only people in this country, but when convenient, apparently employ no one who can be held responsible for their misdeeds. The Sackler family name will remain on the Met and on the halls of the Ivy League institutions I clawed my way into all those years ago, while families like mine will have no justice.