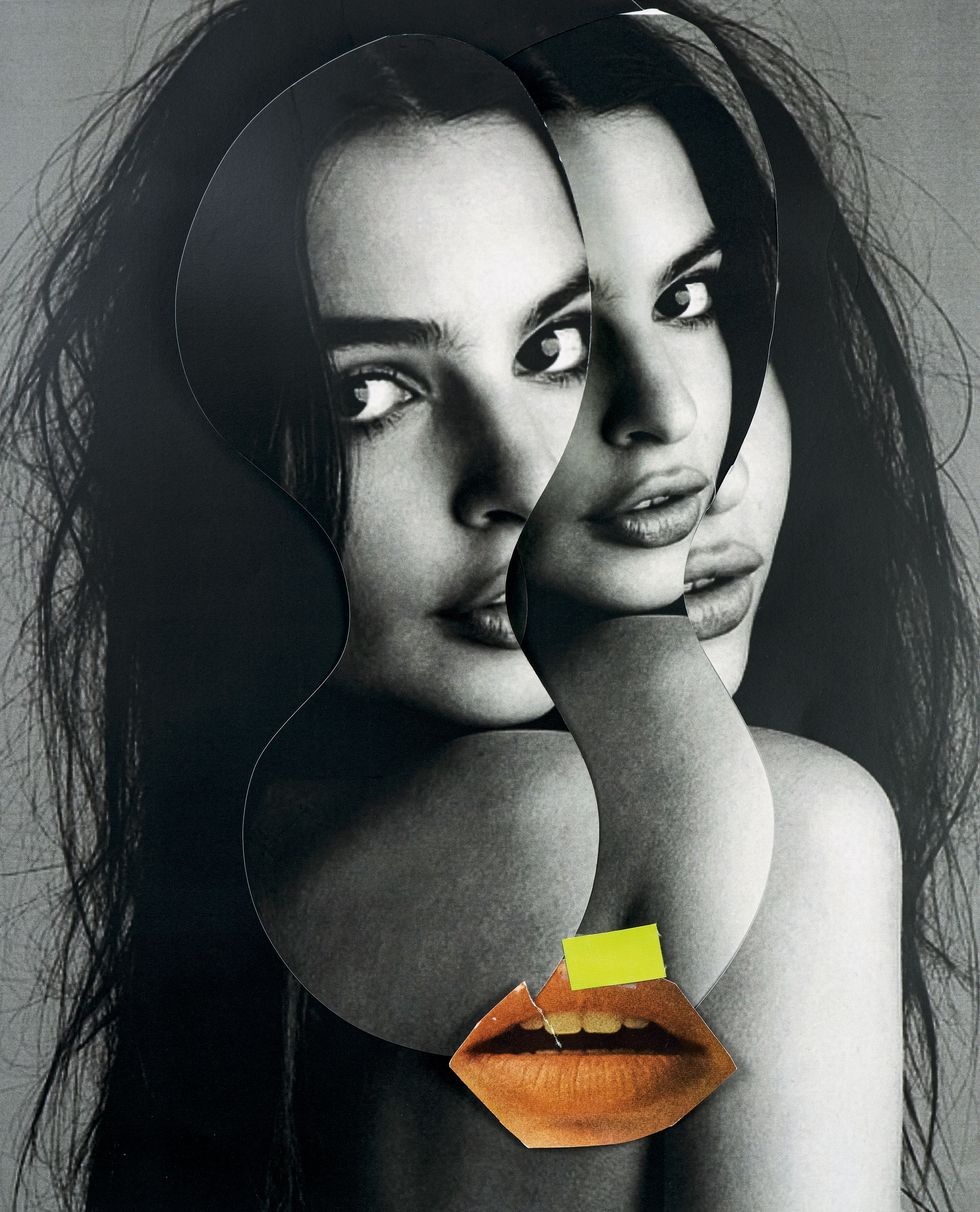

“I want to get to the bottom of things,” says Emily Ratajkowski. “It’s been the blessing and curse of my life.” That scrupulous excavation is evident in My Body, her scalpel-sharp essay collection examining everything from sexual assault to childbirth to objectification. If Ratajkowski had a kindred literary spirit, it would be Lisa Taddeo, whose nonfiction account of women’s sex lives, Three Women, and raw novel Animal cover many of the same themes. Here, the two sit down for a no-holds-barred dialogue.

Lisa Taddeo: You write about your mom rating women’s beauty. My mom used to do stuff like that, too. There were beautiful women and then there were hot women and all those micro-rating systems within [that]. If you hear that at a young age, it fucks you up.

Emily Ratajkowski: I had to work backward in even figuring that out. [With] ex-boyfriends in high school, I would think more about their ex-girlfriends than I would them sometimes. I would look up their Facebooks and never look at my ex-boyfriends’. I wanted to see who was getting ahead or who was last. And I started thinking about how I had gotten there. I think that my mom learned that being beautiful could secure her safety in her relationships and day-to-day interactions. Understanding where she fell in this ranking system was vital to her survival in some ways. There was this internalized male gaze that she was helping me learn without even maybe realizing it. A lot of growing up and therapy [have] made me realize, Holy shit, I don’t need to do this. There’s no winning or losing. But it’s something that I think all young women have to unlearn, or maybe just women in general.

LT: And the idea of women who are beautiful to women versus women who are hot to men—the ranking of that shifts based on what world you’re entering into. Is it a movie that guys are going to watch? Or is it a fashion show where women are looking at the clothes? There’s this moving ideal of beauty that you can’t really even hold on to, and that drives you insane.

ER: You can never win, really. It’s exhausting to compare yourself. It certainly doesn’t lead to any kind of happiness. But there isn’t a woman I know who hasn’t fallen victim to it. I know people who are obsessed with comparing themselves to celebrities, or who still think about that one girl in high school all the time. Even elementary school. We learn this stuff so young.

LT: Men don’t do that. They get jealous in other ways, but I cannot imagine any of my exes or my husband looking up [an ex]... Last night I was talking to my husband about this guy that I went on a weird blind date with when I was living in the city. And I was like, “He was really hot.” The second you say that, guys are like, “What do you mean, ‘He was really hot’?” I found myself telling the story and being really excited that he was feeling like, “Was that guy better-looking than me?” I’m 41 years old; I have a child. As my daughter was videoing herself doing something with the dog, I know she’s videoing my voice in the background, and I’m like, “Holy shit, it does not end. When will it end?”

ER: You write a lot about this—that feeling of “I want to get even.” It’s funny, one of my first interviews [promoting the book] was with a man, and he said something about how you have to have an ice pick in your heart to be a writer. I was like, I guess that’s part of it. I just think that telling the truth of these stories doesn’t take away from the way you feel in your life today. You still want to get a jab in or you still want to win in different ways.

LT: It’s not revenge, so much, but taking the power back was so brilliant. Something that men do a lot, because society permits them to, is talk about an experience they had with you after you’ve become something else in a way that is a complete distortion of the reality. I saw that in your [writing] and I was just maddened by it.

ER: That was what inspired me to write about these things—there’s one perspective that I’m really familiar with, which is the male perspective. Which is, whether you want to say willingly or subconsciously, dismissive of the female reality? I don’t know, that’s a really complicated question and what I’m interested in. But certainly, there’s just no consideration for how these experiences go down for women in those dynamics with men who maybe are not always older, but have a power imbalance. And they’re so unaware of it. I think there is this feeling of, ‘Well, women are so beautiful, they have this power, they have the right to say yes or no to sex.’ It’s so much more complicated than that. I was interested in capturing the nuance that comes with wanting male validation, which you’ve written about so well, especially in Three Women. Where, I don’t know if complicit is the right word, but certainly you want something from them that is potentially extremely harmful. In many of the instances in the book, I’m either modeling or trying to work my way into winning some guy’s attention. I look back and realize the complexity of those situations. I think it’s not about individual men, it’s all men. Because it’s the system; it’s the way our culture works. Women buy into it because that’s how we learn. Even the way we look at other women—that’s because we want power and love and security.

LT: One of the things I always find the hardest to swallow, and the saddest, is that we understand that about each other and about the way we’ve been socialized and sexualized. I’ve always been pragmatic in my working life. I saw something on [Netflix’s] Glow, where she’s like, Don’t ruin it for all of us. Just let the guy think you’re going to sleep with him. I’ve let so many guys think I was going to sleep with them. Would I do things differently now? Yeah, maybe. I don’t know. But what I know is what I did then I did for my survival, in a sense. I have a daughter now. What will I teach her?

ER: I don’t want to tell any young girl that she shouldn’t model or try to capitalize on her image or body. But as I say in the book, I’ve wondered if people would even be reading my book had I not done that. So there is an undeniable power—forget the financial success and fame and all that—but there is just power. People pay attention to you when you get to a certain level. So I was really careful to never say that. But what you see in media, and my own Instagram, is one side, which is beautiful vacations, millions of likes, fancy clothes. And that’s not the complete story. It was so important to write this book and say, Here’s the reality of the whole situation. Here’s the nuance, here are the complicated parts. I start with a John Berger quote: “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity.” Women do it a lot, maybe even more than men. Where they’re like, “Look at her, she’s trying to build on this.” And it’s like, “Well, yeah, of course she is.” The shame that we carry around that is partly why we don’t talk about it more. Because there is so much black-and-white thinking of, “Believe women,” and it’s very easy to slip into this feeling of “All men are predators” and “The world is a scary place for women and how do we protect each other?” And I don’t think it’s that simple. It would be nice to think that way, but it’s not. So I hope that there’s the nuance and also that we [get past] our shame so we can talk about these things.

LT: [With your book], it’s going to be mainstreamed in a way that this conversation isn’t. It’s so heavily nuanced. And we usually, as a country, shy away from nuance. It should be required reading, especially for 16-year-old girls. I think that it’s so important because it’s coming from you. You’d be hard-pressed to find somebody who knows about it more. Like you said, you wouldn’t necessarily tell a young girl not to model. You would say, “If you model, here is what I’ve learned.” Not, “Don’t do this, because I’ve gotten a lot of things from this.” And I think that holding those two things at once is just so vital.

ER: It’s hard now, starting to do press and seeing how things get turned into black and white: “It’s a condemnation” or “She’s complaining about her life.” But I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t share these stories. I write about Britney and what it was like to grow up in the early aughts. I was watching these women as they were getting physically more and more destroyed. Watching these covers of [magazines saying] they look like crap. I still thought that they were on top of the world and that they were winning. Now we’ve come to understand that these women were tortured and continue to be, but [then] it was: “Oh God, they’re messy.” Which comes from this incredibly misogynistic standpoint. But I think that it’s so important to reveal the complexities, because it’s not just famous women, it’s all women. Obviously white women have a very particular position in the world, but it’s all on a scale of what we experience and the ways that we try to work the system and fail at working it. Now we live in a world where everything is about empowerment. That word gets thrown around so easily. But I think we’ve almost lost perspective.

ELLE: Do you think women have more power [on sets] than they did even 5 or 10 years ago, or that there’s just an illusion of power?

LT: We’re staffing Three Women for Showtime, and it is so far [about] 95 percent women—all female directors, all female EPs. But within that, there are still a lot of questions that crop up. I think we have more power now than we did five years ago. But it’s still a male gaze at the end of the day. And it’s still women who are operating under the male gaze. It’s going to take a long time for us to get out of that.

ER: I can’t really speak to the last 5 or 10 years because my position has changed. I’m no longer an anonymous model. It’s not something that when you’re 22, you can necessarily be aware of in the same way that you can when you get older. I do think some things have changed. But I don’t know that it’s for the right reasons. We live in a culture where people are acting out of fear of consequences, rather than learned respect. You don’t teach a child to not hit their brother because they’re going to get a time-out, but because it’s not a nice thing to do. Everyone is worried about the time-out rather than actually understanding empathy. That’s why I think writing is so important, because it’s not the Twittersphere and the really quick cancellation. I think storytelling brings out people’s empathy in a different way. So I’m hoping that a lot of men read this book. I don’t know if that’s going to happen, but I would love for that to happen. It shouldn’t just be that once a man becomes a father to a daughter, he starts to understand these things.

LT: That’s brilliantly put, the fear of the time-out. We are just like toddlers at the end of the day.

ER: I have a son now, and I’m starting to think about what our instincts are. Forget even boy/girl, but just, What are human beings’ instincts? How do you encourage a person to feel confident, to like who they are, while also teaching them about what’s nice and what’s not nice? It’s like with voting: “You have to vote. It’s your job.” Well, maybe we need to make sure that the candidates are better and the political system feels like it’s earned our trust. Again, it’s this lack of nuance. It’s amazing how much I’ve learned about Afghanistan in the last two weeks just from being on social media. But they’re quick, one-sentence things or really shocking images. There’s not a deep understanding. There’s a peripheral level of how we consume media now that’s dangerous.

LT: When it comes to the people you’ve named [in your book], it feels relentlessly brave. It feels like you wrote this book in a vacuum, which is the way that I think books should be written, without fear. Was it a scary decision? Because I admire the hell out of every part of that.

ER: Yes, I’m still absolutely terrified. The essay with Jonathan [Leder] was published, and that’s an essay about a lot of things. And, of course, the headlines were like, “Emily Ratajkowski accuses blah, blah, blah.” It was really hard to see that: “Wait, this is a 7,000-word essay that I poured my guts into and now it’s just a clickbait headline.” [Editor’s note: Ratajkowski accused photographer Jonathan Leder of sexual assault in a New York magazine essay; Leder’s representative told USA Today that he “completely denies her outrageous libelous allegations of being ‘assaulted.’”] I also met Jonathan’s children and was thinking about them having to face my reality of how I experienced their father. I feel the same way about other men in the book. In my dream world, what would happen is not that people are canceled, because what does that even mean? Ultimately, people go on living their lives. The people who are close to them love them. They have a right to exist and to live a wonderful life. That being said, I think that there is this canceling thing that happens. My dream would be that we’d live in a world where rather than blaming this individual and saying, “We’re casting you out of society; that will make things better,” we take a larger look at what allowed this kind of behavior. If I were a different person, if I were not well-known in other ways, I would not have mentioned specific names, but for these stories to feel real and for people to understand the full situation, I had to give names. It was the difference of, somebody could Google them or not. There are other moments in the book where I don’t name people, where I feel like it’s not important who it was. But I think in [some] instances, it’s pretty important for the reader to understand. I have a hard time with the power that the world gives you when you tell your story. Instead of learning the lesson, there’s this black-and-white thinking again, where it’s like, Well, that person is just done. I really don’t want that for anyone because I also, again, believe it’s not all men and it’s also all men. I think everybody’s father, brother, whatever, has at one moment or another—it’s, again, on a scale—but they have unknowingly, or maybe just because it was convenient, taken advantage of their position in the world. That doesn’t mean that everybody is bad and needs to be cancelled. It just means that we need to be more aware.

LT: Any thinking person will be able to read it as an exploration rather than a condemnation. Humans make mistakes, and that’s how you framed it. Obviously, people will do clickbait-y stuff. But I think you did a perfect job of not doing that, or not creating an environment for that, but doing the exact, necessary opposite.

ER: I worked really hard to take out any punishing in the writing. It’s not always the people who you would think are the quote-unquote bad guys. It’s people who are close to you and you’re like, “This sentence doesn’t need to exist here. Why am I punishing this person?” I don’t want to say that there isn’t an instinct—like your experience with your husband and trying to make him jealous. I think it is important as women to realize that we’re pissed off. There is a feeling of, I want to burn this motherfucker to the ground. I think [it’s about] finding the balance. Because I don’t want to punish, I want to tell the truth. That’s it.

ELLE: You write about seeing a therapist to learn to physically express anger. Did writing help you channel that anger?

ER: No. I’d be lying to you [if I said that]. But that was one of the hard things about writing the last essay. There is a tendency with books to tie everything up in a bow and go off into the sunset. And that’s just not how I feel. But what was important to me was finding these moments of release, or moments where I’m connecting to my body through anger, which can be really powerful if it’s not used to punish someone. I’m breaking something against a wall, not breaking somebody. The reason I set out to write was to deal with my shit, absolutely. With the essay that was published in New York magazine, I was so nervous. The week before, I couldn’t sleep. I was sobbing. I was an absolute mess: “Why did I do this? Remind me why I wrote this and why I’m deciding to publish it?” And then when it went out into the world, it was cathartic. Because all of a sudden, it was people recognizing my reality. It’s so validating. I didn’t have that for a big part of my twenties, whether in these small interactions that I write about or on a global scale. To be able to say, “This is my story,” it’s very healing.

LT: All the books I like are written by women who don’t give a fuck. I always think it’s interesting whenever people talk about female main characters being likable or not. I don’t need to be friends with someone in a novel. I want to understand more about myself from a novel. I think if you just say everything honestly, it sounds like anger. But we also add that little coda of rage to a woman just expressing herself. It’s rage if she’s not going along with the status quo. We have been tamed into doing the status quo at any cost, or we are out of line. I found a voice early on that felt like a voice that didn’t give a fuck. Obviously, I’ve gotten some shit for that, and it’s fine. But I didn’t want to write a book that I didn’t want to read.

ER: I loved your essay in the Guardian about female rage. Because I do think there’s this fear that we have of turning into this ugly, angry witch. And I’m totally scared of that. Not enough people have read the book yet—but I could imagine people saying, “She’s so angry.”

LT: It doesn’t come off as angry. There are moments of anger, but it all felt clearheaded. I think it’s so phenomenally calibrated.

ER: [The fact] that I’m even so afraid of it is interesting to me. What’s wrong with being angry? I think some anger is justifiable—more than justifiable. I don’t think that women should be afraid of that.

ELLE: There’s a running theme in both of your work about women struggling to understand their desires, and the difference between seeing yourself as an object of desire and actually desiring. What have you learned about that question through exploring it in your work?

LT: I will say that I have a really hard time with it. If I don’t feel attractive, I’m going to have a hard time being excited to have sex. I admire so much women who do not. It’s something I strive to feel. Right now, I’m probably at the worst I’ve ever been in terms of how I feel about myself. It’s been really difficult for me because I was raised on ’80s movies, and it was all about the way a woman looked, and I have internalized that.

ER: I’m somebody who’s expertly internalized the male gaze, and then turned it on myself enough to make a living off it. In the last essay, I had the piece about breaking stuff—and then birth. I couldn’t figure out a moment where I’ve been in my body and not self-aware on some level. It took me weeks. It was the hardest chunk of the book to write. And it’s just a bike ride with my husband and my best friend. Because it hit me: I was using my body. I wasn’t floating above myself, thinking about how I looked. I was just in the moment with people I love and who love me. That’s the goal: to have more of those moments, sexually or otherwise. I don’t think it’s going to come easily to any woman in our culture. But I think that it can happen, through figuring out who you are, and then sharing it with people you love. Then intimacy, physical or otherwise, becomes less self-aware.

LT: For me, it’s also been physical activities like that. Going into the ocean—in those moments, I’m like, Oh, wow. So this is what it’s like to have no shit [laughs].

ELLE: The book ends with a completely different function of the body: childbirth. How has motherhood shaped your outlook? Did it change your relationship to your body?

ER: I was unsure if I wanted to end the book with motherhood, because I hate the idea that you become a mother and everything changes. It’s something I talk about in the book: You go from child to sex object to mother. But it was one of the most powerful physical experiences. Being in a room and trusting my body—even though there are people around me who say that they know it better than me or that they have a right to it in some way—was hugely impactful. It wasn’t until I was rereading the whole book that I realized that at the beginning, there’s an essay about not being able to say no. And then in the hospital, I say no, my body responds to me saying no, and I give birth to my son. Writing these essays allowed me to get to a place to be in that room and be connected enough to my body to be able to say, “No, we are not going to use the vacuum.” Then my body’s like, “She just said no. We’re going to deliver this baby.”

LT: I feel the same way. The idea of, you’re a little girl, then you’re sexualized, then you’re a mom, then you’re dead. Whereas men get to have their full cycle, and it’s biologically unfair. Motherhood changed me in all the ways that it does, and then in a lot of ways it didn’t. My daughter is six, and I sometimes see the way that men look at her. She’s blonde, she’s got giant blue eyes, and I’m so hyper-aware of it, because of having experienced my own stuff in the past. I’m always staring at my daughter, looking to see where the danger might be coming from. That is such a frightening thing, that I’ve now put the male gaze on my own daughter. It haunts me.

ER: I wanted a daughter initially, but when I found out I was having a son, I was so relieved. Because I think that it would bring up—I want more children, so it might be something I deal with later—being sexualized way before puberty and being aware of it. I have a memory: I did a sexy move down the wall of my parents’ kitchen. I was probably in first grade and my parents were like, “Where did you learn that?” I was like, “I fricking learned it. That’s what women do.”

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

This article appears in the December/January 2022 issue of ELLE.

Véronique Hyland is ELLE’s Fashion Features Director and the author of the book Dress Code, which was selected as one of The New Yorker's Best Books of the Year. Her writing has previously appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, W, New York magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, and Condé Nast Traveler.