This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, and co-published by Native News Online.

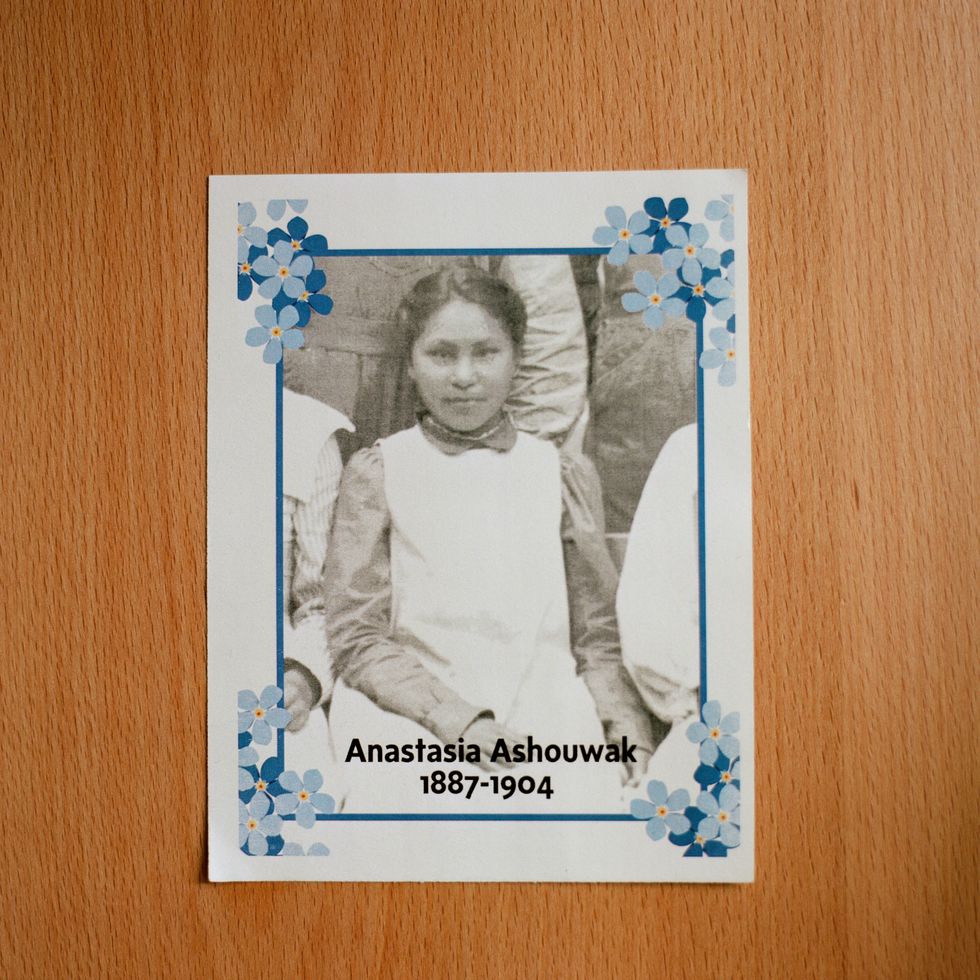

Descending from the sky, the remote village of Old Harbor, Alaska, appears in vivid color, dwarfed between a screaming-green mountainside and a spit of ocean. Anastasia Ashouwak was away at Indian boarding school for 121 years before the wheels of our propeller plane carrying her remains touched down in early July.

On the runway below, more than a dozen vehicles idle, filled with residents waiting to welcome home a distant relative they only recently learned they’d lost. Children sit in the bed of pick-up trucks and dangle out of windows, silently watching adults who work in a line, unloading the cargo from the plane: paper goods for the potluck, a frosted cake with Anasasia’s name emblazoned in pink icing, and finally Anastasia herself. Her remains are carried in a small coffin, painted sky blue and decorated by her descendants to mimic Sugpiaq/Alutiiq petroglyphs. (Sugpiaq is the oldest term that Indigenous Kodiak islanders use for themselves, meaning “Real Person.” Alutiiq is a self-designator formed by Native speakers from the word Aleuty, a term used by the Russians for most coastal Native Alaskans. Both terms are in popular community use.) “It’s just amazing that this happened,” says Lloyd Ashouwak, 60, of having her remains returned.

Lloyd is Anastasia’s direct descendant through his late father, who was Anastasia’s nephew. He and his brother, who were born about 70 years after Anastasia, only learned of their relative who was buried across the country when the nearby Alutiiq Museum, which is leading a repatriation project, reached out a year ago. Although Lloyd grew up hearing stories about his grandfather, Peter Ashouwak, he never heard of his aunt Anastasia, who was taken away to Indian boarding school at 13-years-old. “It’s like losing a loved one you’ve known all your life,” Lloyd says as her coffin is lowered into the ground, beside her brother Peter, and her nephew, Lawrence Ashouwak, at the oceanside cemetery. Though none of the residents knew her, they could have been her. “The feelings are the same: sad, mad that this happened, joyous she’s home,” Lloyd says.

Anastasia was one of at least 100,000 Indigenous youth removed from their families and communities—some as young as three-years-old—and sent to boarding schools as part of the United States government’s 150 year policy to assimilate Native youth, according to an estimate from historian David Adams in his book, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. No official count has ever been conducted though, and Alaska Native scholars say that total is likely far higher. Such schools were “designed to separate a child from his reservation and family, strip him of his tribal lore and mores, force the complete abandonment of his Native language, and prepare him for never again returning to his people,” according to a 1969 report by the US Senate Special Subcommittee on Indian Education.

Sickness, neglect, and abuse was rampant at many of the institutions, though it was brushed under the rug and only recently distilled in an initial investigation into Indian boarding school history. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland of the Laguna Pueblo, the first Native American cabinet member, launched the investigation last June. The report, released eleven months later, found that at least 500 Native children died at boarding schools throughout the country. The death toll is expected to rise to the “thousands or tens of thousands” with continued review of the more than 400 boarding schools run or paid for by the U.S. government. Twenty-one of the Indian boarding schools were in the state of Alaska.

In 1879, Carlisle Barracks, a former military outpost in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, became the site of the nation’s first government-run boarding school for Native American children. Twenty-two years after its opening, in 1901, Anastasia Ashouwak and 10 other Alaska Native children were taken by a government agent from a Baptist Mission orphanage in Southwest Alaska to Carlisle Indian Industrial School, some 6,000 miles away.

The Carlisle school was operated by the Department of the Interior until 1918, under the motto of “kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” and worked to forcibly assimilate 7,800 Native American children from more than 140 tribal nations through a mix of Western-style education, hard labor, and language and culture eradication. At least 186 children died there, of disease often made worse by poor living conditions and abuse. Anastasia was one of them. Her records say she was studying “housework,” and that she was loaned to a local farm during the summer as a servant. She died of tuberculosis three years after her arrival, at age 16. She was then buried on school grounds, under a headstone that misspelled her name as ‘Anatasia Achwack.’

Now, she is among the first two dozen children to be returned home to their next of kin. On July 6, the U.S. Army—which took over the property from the Department of the Interior when the boarding school closed—disinterred and returned Anastasia’s remains to four of her family members at a transfer ceremony in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

The U.S. Army began returning a few children a year beginning in 2016. Its decision to do so is largely thanks to the work of a Northern Arapaho Tribal member, Yufna Soldier Wolf, who won a 10-year battle to bring home three Arapaho children who are now reburied on the reservation in Ethete, Wyoming. Repatriation, or the return of someone to their own country, is a key factor in a larger moment of reckoning by a United States government that is just beginning to look at its own role in the atrocity of Indian boarding schools.

Since last year, the Army has taken a more proactive approach of returning the Native children buried in its graveyard by contacting the tribes of the children that remain buried at the Carlisle Barracks to help locate direct descendants. That’s how the Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak learned about Anastasia, and how the Ashouwaks came to learn they had a relative buried at Carlisle.

Since 2017, the statewide nonprofit First Alaskans Institute has been focused on acknowledgment of the truths of the past and generational trauma. First Alaskans Institute President Liz La quen náay Medicine Crow (Haida/Tlingit) spoke at a Senate Committee hearing in June of 2022, and stressed the importance of collecting oral histories from survivors while they are still able to share them. Medicine Crow advocated for the passage of a bill that would establish a federal Truth and Healing Commission that would investigate the impacts and ongoing effects of the Indian Boarding School Policies. “While we focus on the importance of the children who were taken, it is also incredibly important to focus on the communities that they were taken from,” Medicine Crow says. “I often wonder: what would it be like to come from a place with no children? This is what was imposed on our people.”

Despite the atrocities committed at boarding schools, they did not succeed with their goal of stamping out Native culture. Instead, Anastasia was welcomed home with traditional Sugpiaq/Alutiiq dance, dress, food, song, and painting. “It was to honor her,” Cassey Rowland, Anastasia’s great-great niece, says of the cultural aspects included in the Pennsylvania ceremony, and amplified at the local ceremonies in the hub City of Kodiak, where Anastasia’s remains had a stopover, and again in her home village of Old Harbor.

Rowland had traveled from her residence on Kodiak Island to Pennsylvania to receive Anastasia and bring her home, “to show her that she was loved, and that we were bringing her home, where she was wanted. Even when she was born, our culture was being stripped from us. I felt like showing her that our culture is still strong.”

At the official transfer ceremony at Carlisle Barracks, I meet Bayley Rowland, Cassey’s 13-year-old-daughter, who is perhaps the most powerful evidence of resistance to the government’s policy. She sits straight-backed in full regalia facing her great-great-great aunt’s coffin, which she helped paint the day before. She shares the same birthday and strikingly similar facial features with Anastasia, a connection that her mother says made their direct relation to Anastasia feel ever closer. Bayley is also the same age Anastasia was when she was taken 6,000 miles away from home.

In many ways, Bayley lives the life that Anastasia could not: she attends school down the street from her home in Kodiak, where she takes online Alutiiq language classes with her mother; she makes contemporary versions of the beaded jewelry her ancestors wore, selling it at the Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak; she’s been part of a traditional Alutiiq dance group since preschool; she learned from her mother and grandmother how to forage for different plants to make medicinal salves, and has been labeling jars of smoked fish her grandmother puts up since she was three. “We’re a culture of strong women. We still are,” Bayley’s mom Cassey says later, on her couch back in Kodiak. Cassey is an artist who has made her culture her livelihood. Her home is evidence of her work both as an Indigenous artist, and a dedicated single parent. Sea otter pelts waiting to be cut and sewn decorate the couch, traditional Sugpiaq beaded headpieces sit on a mannequin behind glass, and plastic drawers hold beading materials for earrings line the living room. On the wall beside Bayley’s bedroom, a sign gifted to Cassey by a friend reads, “Here’s to strong women. May we know them, may we be them, may we raise them.”

Rowland says that her goal as a mother is to break the cycle of trauma stemming from a violent history of colonization, including through boarding schools, and passed down to her people across generations. The term ‘historical trauma’ was first coined in the 1980s by Native American social worker and mental health expert, Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart (Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota) as a way to conceptualize the “physiological wounding, over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma.”

When historical trauma is not resolved and instead is subsequently internalized, Brave Heart surmised, it begets ‘‘intergenerational trauma’, which is then passed on to a traumatized person’s descendants, sometimes unbeknownst to them.

Her research suggests that such trauma manifests itself in poor health outcomes plainly apparent across Indian Country, including disproportionately high rates of cancer, heart disease, diabetes, alcoholism, and suicide. Healing from historic and intergenerational trauma, Brave Heart explained, might be helped by reattaching to traditional Native values, and also by understanding the relationship of the past to that of the present.

“Everybody kept secrets in the past, we weren't allowed to talk about anything about our culture,” Cassey says. Her father, Ted Ashouwak, told me he attended a regional boarding school in Kodiak for high school, where his host family often starved him. Until the mid-70s, there was a single high school that served Kodiak’s six remote villages. That changed the year Cassey’s mother was set to attend high school from her village, when 27 teenage plaintiffs won a lawsuit against the state for not providing high schools in Alaska Native villages. As a result, she was able to stay in her village for high school.

“Our generation doesn't know about [boarding schools], because the older generations wouldn't talk about it,” Cassey says. “That's why we didn't know about Anastasia.” But Cassey doesn’t hide the truth from Bayley. “I'm pretty darn open with her about everything,” she says. “I teach her to be proud of who she is, whereas when I was growing up I was told that it’s not okay to ‘act Native.’”

Kodiak, like the rest of Alaska and the country, is at the beginning of its realization and healing. “Every single one of us had family members that went to a boarding school,” says Alutiiq Museum Executive Director April Counceller. She was part of the working group to bring Anastasia home, composed of family, Native leaders, and clergy members. “We don't know how many people that totals up to.”

Anastasia is the first child to be brought home to Kodiak Island from a Native boarding school, but it’s inevitable she won’t be the last. The Alutiiq Museum is in the process of claiming another Sugpiaq/Alutiiq girl, Perascovia Friendoff, who was taken to Carlisle with Anastasia and also died of tuberculosis. Because the museum was unable to find documents to tie Perascovia to her living relatives, her repatriation was delayed, and is tentatively planned for next summer, Counceller says.

Since the repatriation is just beginning, Rowland says, it’s hard to know the scope of the healing that will be necessary for her community. In just her own family, learning about Anastasia has led to additional discoveries of family members buried at or near boarding schools, including her great grandmother who attended Chemawa Indian School in Oregon. “If more family members start showing up, heck yeah, we’re gonna need some healing,” Rowland says of her community. “I'm honestly still overwhelmed with these big feelings from this trip, and still processing them. In closing [Anastasia’s] circle, it’s opened up so many more.”

After three days of dense fog that shrouded Kodiak Island, the sky cleared, and a nine-seater plane took Anastasia 30 minutes down the southeast coast of the island to the village of Old Harbor. Under the blue dome of the Russian Orthodox Church in Old Harbor, a priest invited on Anastasia’s repatriation journey, Father Innocent Dresdow, tells locals the story of Anastasia’s short life. “Nothing can be done to right the wrongs. We can't go back and rewrite history,” Dresdow says to the residents of Old Harbor. “But [we] can do this. I pray for each and every one of you gathered here today that this will be a healing moment as we give her a proper burial.”

After mass, a procession of community members follows Lloyd Ashouwak, with Anastasia’s coffin on his shoulder, up the grassy hill beside the church to the cemetery. Barking dogs weave between feet as a group of Alutiiq dancers perform for Anastasia. A few elders weep, while bored kids wander towards ripe salmon berry bushes. “It’s really incredible,” says Trinity Inga, 22, still wearing her Alutiiq facial markings across her cheeks and chin. “It’s the history of our village, and actually being able to bring someone back that was taken from here is heartwarming. We couldn't ask for anything else, except to bring her home.” One boarding school survivor, 71-year-old Carol Christensen, adds the question nobody is able to answer: ‘What took so long?’

Later, the village comes together in the local bingo hall to feast on smoked salmon, fresh bread, meatballs, and other potluck dishes. Residents echo words of “finally” and “home” and “healing” as they dig into the frosted cake that could be mistaken for a birthday cake. It’s for Anastasia. Under her name, only her birth date is written, a seemingly an intentional gesture towards eternal life. “It’s going to open people’s eyes,” Lloyd Ashouwak says of his great aunt’s homecoming. “They’ll say ‘where are the other family members?’”

Jenna Kunze is a New York based journalist covering stories impacting Indigenous peoples across the US and Canada.