On Monday, March 1, 2021, at around 4 P.M., the Piper Breast Center in Minneapolis called me about a test I had taken the Friday before. I don’t remember the name of the woman who called. I don’t even remember her job or title. I just remember what she said.

“I am calling with your test results from the biopsy you had Friday, which was a follow-up to the mammogram you had a week before at Mayo Clinic. The earlier test showed spots and calcification. The biopsy we just did shows us more. It turns out you have breast cancer. It is Stage 1A, which is better than some other stages, but it is still cancer. You need to find a breast cancer specialist, and then they can map out a treatment.”

“What will the treatment be?” I asked, vigorously writing everything she told me on a small yellow Post-it Note.

“Well, that you need to discuss with a doctor. It can be everything from surgery to radiation. You need to talk to a doctor right away.”

“Okay,” I said. “Are you going to call a doctor right away?” she asked. “Yes,” I said, “I’m on it. Thanks for letting me know.”

I pressed the “end call” button on my cell. “I’m on it”? “Thanks for letting me know”?

What I really wanted to say was this: I have votes on the Senate floor in a half an hour. I have to walk into the Senate chamber and pretend nothing is wrong in front of a bunch of guys. Senator Durbin wants to meet with me about a bill. I have work to do! A year ago I ended a presidential campaign and then devoted myself to helping someone else win. I have made it through an insurrection and have done everything I could to make things better. Why this? Why now? My husband almost died of COVID. I have picked up the pieces of my life. It’s just the wrong time in my life to deal with this. We are in the middle of a pandemic. How am I going to get help? I’m leading an investigation of what went wrong on January 6th with U.S. Capitol security. It isn’t something I can just put off for another day! Am I going to have this “treatment” and still be able to lead those hearings? I mean, these hearings are really important. Where should I go to find a doctor? What does “1A” mean? It sounds like an apartment unit. Do I need chemo? Am I going to have to wear a wig? How bad is this surgery? What are my chances? My dad is dying. Can I be there for him?

But all I said was, “I’m on it. Thanks for letting me know.”

On March 30, I had the surgery. With my husband at my side, I headed to the big revolving doors and the lobby of the Gonda Building on the Mayo Clinic campus, a place near and dear to the hearts of many across the nation and the world and a point of pride for my state. It was all so, so, so professional, yet part of me wanted to scream through my smile, “Everyone is so nice and calm, but you are going to take out a chunk of my breast, and you just drew a target on it!”

Having talked to other women who have been through breast cancer surgery, I know they have had similar experiences. But I did have one unique pre-op moment most likely not shared by others: I was about to head into surgery when someone recognized me and—as constituents have every right to do—used the minutes she had with her senior senator pinned down on a pre-op rolling bed with clearly no means of escape to make her case for the people of Burma.

It was of course legit: a lot of bad things were happening in Burma at the time, and we had already helped a number of refugees. “I promise,” I said, my double hospital robes concealing the penned-in target on my breast, “I will look into it when I’m done here. I’d do it now, but they won’t let me have my cell phone.”

As they put me under the anesthesia, I drifted away, not to the calming count of pastoral sheep, but instead to the obsessive mantra: “Don’t forget Burma. Don’t forget Burma.”

Hours later, I emerged from surgery, and [my husband] John was there with a nice card from my kind primary doctor, Janet Vittone, and a plant. I felt a bit sick, but through the grogginess of the post-anesthesia fog I did manage to immediately focus our conversation on two critical things:

Me: “Was it just a lumpectomy, or did I need a mastectomy?”

John: “It was just a lumpectomy!”

Me: “Could you get my phone so I can text the staff about Burma? There was someone I met before I had the surgery…”

John: “I guess you’re doing okay then.”

The Burma moment was a precursor of things to come. During the week after the surgery I would continue with my public events in Minnesota, which—in hindsight—was really stupid. The doctors sagely told me not to do so much, but I did it anyway: a Lake Superior port expansion event in Duluth, a vaccine press conference in a suburban hospital, numerous staff meetings and Zoom calls. Senatorial habits are hard to break, even following surgery.

For the most part, because of the pandemic, the events I did were outside and cold, with participants donning thick winter coats. COVID protocols meant that few people were greeting me with hugs, which would have been bad, because they would have really hurt. We’ll call that a pandemic silver lining.

To keep my own dignity (not to mention the dignity of my office), I will spare you most of the details of the surgery and post-surgery experiences, except one that is so common among women with this kind of cancer that it would be an insult to all of us (and you know who you are, because I’ve talked to many of you) not to mention it.

For various reasons (which again, we do not need to explore in nitty-gritty detail), the surgery and the medication decisions in its aftermath triggered months of hot flashes, which are inconvenient for any woman, but particularly vexing when you are right out of surgery and things you thought had ended are suddenly saying: “Surprise, surprise: I’m B-A-C-K!”

Consider being a U.S. senator surrounded by men who have no idea what is going on. It is a recipe for hard times and dark thoughts: “These guys have no idea what I’m going through, and I wish it happened to them once. Like right now, when that guy is giving that obnoxious speech.”

The hot flashes keep you up at night and drive you especially nuts during hot weather. I personally believe that if men experienced menopause and hot flashes, there would be a whole lot more research and potential solutions, but for cancer patients, there are currently limited remedies outside of not very useful medications with side effects that made them not worth it for me. There were also organic remedies and homespun treatments that in my case had no effect (but go for it if they help you) and nightly visits to the freezer. For guys that can’t relate, yes, I mean PUTTING MY HEAD IN IT.

Now one positive: my post-surgery hot flashes were invisible to nearly everyone but me. Except once. I remember one amusing call from a fairly famous person in May, just a few months after the surgery. She called to tell me I had “looked really good on Colbert.”

“Glowing,” she said, repeating with emphasis, “glowing.” She added, “What is your secret?”

Wow. I recalled the Stephen Colbert antitrust interview, knowing immediately I would not share with her the cancer diagnosis. Instead I decided to break my vow to myself to keep everything quiet with one big reveal. I mean, how often do you get asked—after decades on this earth—what your fountain-of-youth beauty tip is?

“Hot flashes,” I said. “Hot flashes.”

“Because of the home pandemic-era ring light beaming on my head [I had done the Colbert interview by laptop from my D.C. apartment], I had not one, not two, but three of them during the ten-minute interview.”

“Oh my,” she said, “oh my.”

“But it looked really good anyway,” she gushed. It was moments like those that kept me going, right through to radiation.

One of the hardest parts about the whole thing was that the week of radiation coincided with losing my dad. On one horrible day I literally came back from radiation to pick out his tombstone. But the months leading up to it had allowed me and my family and all his friends and my uncle Dick and his family to say goodbye. My dad held court for months at the assisted living memory care unit, telling old stories (a few of them were even true) and sharing tidbits of wisdom and his faith in God to the very end.

The life perspective for me as I witnessed my dad slipping away with late-onset Alzheimer’s while battling my own breast cancer? My dad had experienced a life well-lived, a life of service.

There was so much to rejoice in, even to the end. If I found myself temporarily down over his inability to remember my name or even where he was at the moment, his singing of hymns, Christmas jingles, musical tunes, and yes, drinking songs would jar me into a smile no matter where my mind had wandered.

And even through the Alzheimer’s, somehow my dad’s wit and insight never left him. In addition to John and Abigail and me, his many visitors during that last year included his brother Dick, my sister Meagan, and his many friends—including Pastor Mark Hanson, Rod Wilson, and Doug Kelley. Every one of us has joyful memories of our visits during those last few months of his life.

“What a nice day it is today,” I would say, opening the shades to his little room in an assisted living facility in Burnsville, Minnesota. “I’ll second that f-ing motion,” he would punchily reply as if giving the laugh line from a story well-told decades ago in the press box at a football game.

During that week of my dad’s death and leading into the radiation, my colleagues were wonderful. Their help ranged from the small—Thom Tillis’ nice staff letting me use his conference room for an hour after I ran out of a Commerce Committee legislative markup, because I had just found out my dad died—to my Judiciary Committee colleagues easily passing out one of my antitrust bills. Calls and notes arrived from many. While they didn’t know I had cancer, they truly rose to the occasion.

And then there was the medical staff at Mayo…the doctors and nurses and nursing assistants and technicians who allowed me to grieve for my dad, kept my story mine, and, through their good work and expertise, made my future mine, all at the same time. I still have the little red radiation pin the radiology techs gave me when I “graduated” and the red-white-and-blue-flag mask they found for me to wear for Memorial Day.

By the end of August I’d decided it was time to tell my story. As was confirmed again by tests I had a few months later, the doctors at Mayo told me that I was 100 percent cancer-free and that my chances of getting cancer again were the same as the average person’s getting cancer in the first place. I don’t know who that average person is, but it sounded good.

On September 9, 2021, I put out a simple statement explaining the diagnosis and my health status. I did an interview with Minnesota’s Star Tribune newspaper. I went on Good Morning America with Robin Roberts; she too had been through a public bout with cancer. My message was simple: get your exams, and go in for the mammogram you may have delayed. I delayed mine but finally got it, and I still caught it early.

The outpouring of stories, tweets, posts, and calls to our office from women who had put off their exams and were now scheduling an appointment as a result of my news was unbelievable. Several women texted me from waiting rooms to tell me they were there for their mammograms. And then, sometime later, a letter to our office came from a woman in Maple Grove, Minnesota:

Just wanted to thank Senator Klobuchar for going public with her breast cancer diagnosis and reminding women to get their mammogram. Because of her reminder, I made an appointment. From that appointment, the mammogram found a lump and after several tests, I’ve been diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer. I am thankful that we caught the cancer early and will fight to overcome it. Sincerely, Melissa

Through it all I learned one practical lesson: there is rarely a good time to go in for a mammogram or any other routine exam. People are constantly balancing their families, their jobs, and their health. It’s easy to put off health screenings, just like I did. But I hoped my experience would be a reminder for everyone of the value of health checkups, exams, and follow-throughs.

As often happens with anyone dealing with illness, this experience also gave me time to reflect on my life and those I love. It gave renewed purpose to my work. I have immense gratitude for my family, friends, colleagues, and the people of Minnesota, and I know that each day is a gift, a joyful gift.

Perfect strangers who did not know I was sick helped me during those hard months. I would get on a plane from D.C. to Minnesota full of cranky mask-wearing passengers, knowing I wasn’t supposed to lift up my luggage for three months but not wanting to explain why. I would pause for just a moment, and every single time a Good Samaritan I did not know—and who did not usually know me either (the then-mandatory masks make great disguises for politicians)—would jump up and push in the heavy suitcase filled with clothes and notebooks and briefing papers.

The final lesson I learned? You start where you are.

This one came out of a sermon I heard that summer of my recovery at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, the one where the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. preached, and where my friend (yes, truly my friend) Senator Reverend Raphael Warnock is the senior pastor.

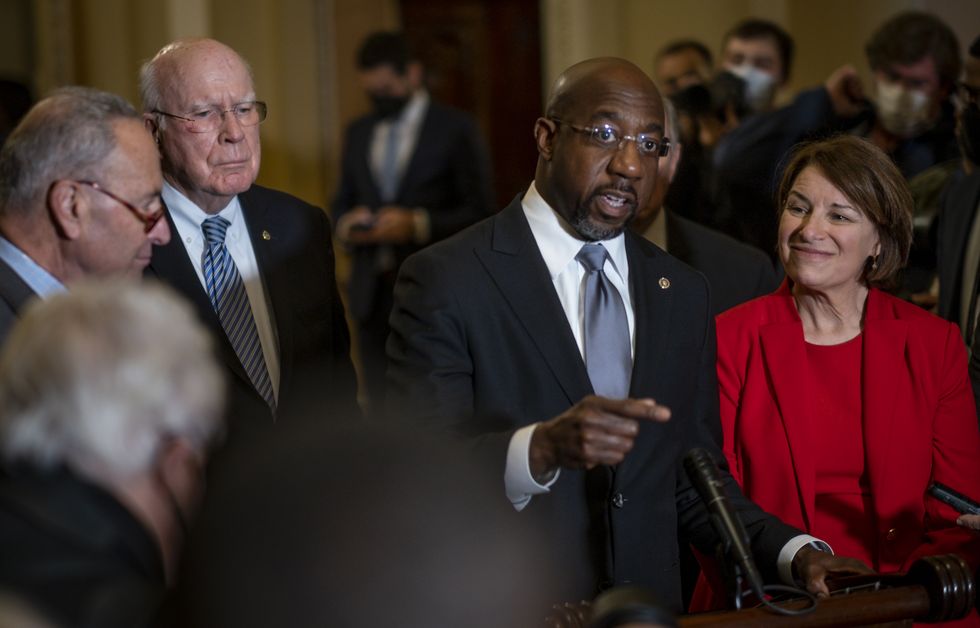

That weekend Reverend Warnock was our host in Atlanta for the first Senate Rules Committee voting rights field hearing in decades. As the brand-new chair of the Senate Rules Committee, I felt we needed to take the committee on the road and hear testimony about state-passed obstacles to voting. My colleagues (Senators Warnock, Ossoff, Padilla, and Merkley) and I heard numerous witnesses testify in support of passing federal voting legislation.

The visit to Reverend Warnock’s historic church the day before the hearing was his idea, and I was honored to join him. That Sunday it was “Women’s Day,” and there was a guest minister preaching: Reverend Claudette Anderson Copeland, from a church in San Antonio, Texas. She herself was a survivor of serious cancer, something I did not know until she mentioned it at the tail end of the sermon. As I sat there next to Reverend Warnock, with no one in the church knowing that I was going through cancer treatment, her words stuck with me, and still do today.

“Start where you are. Begin. Commence. Get going. Crank up. Initiate. Mobilize. Start where you are.” “Never be intimidated by external indicators. The mortgage rate’s too high. Weather too hot. Your body too sick. You think you’re too young, too old, too Black, too white. Some of us are so discouraged by where [we] want to be. It appears so distant and so far away and so unlikely. The dreams seem so expansive and the horizons seem so far. It feels like you won’t ever get it done.” “You’ve gotten stuck in your reality at the expense of your possibility.” “Subversive shifts begin with one small beginning.” “Don’t stay hamstrung by your yesterdays, harnessed and muzzled by who hurt you, who failed you and who dropped you and who quit on you and who cheated on you and who left you.” “Bust the move, and start where you are.”

I heard those words just a month after I’d gone through radiation. And in that moment, in that church filled to the brim with the joyful music of worship and the reverend’s resounding voice, I felt like I was finally ready, five months after getting the call and finding out I had cancer, to find solace in my faith in God, to accept the setback, to take it as it was, and to start where I was. That moment in that church was it. I realized that the only way I could have the strength and the faith and the firm footing to move forward was to start where I was, not where I had wanted to be a year before. Not where I had planned to be before I got the call.

But just where I was.

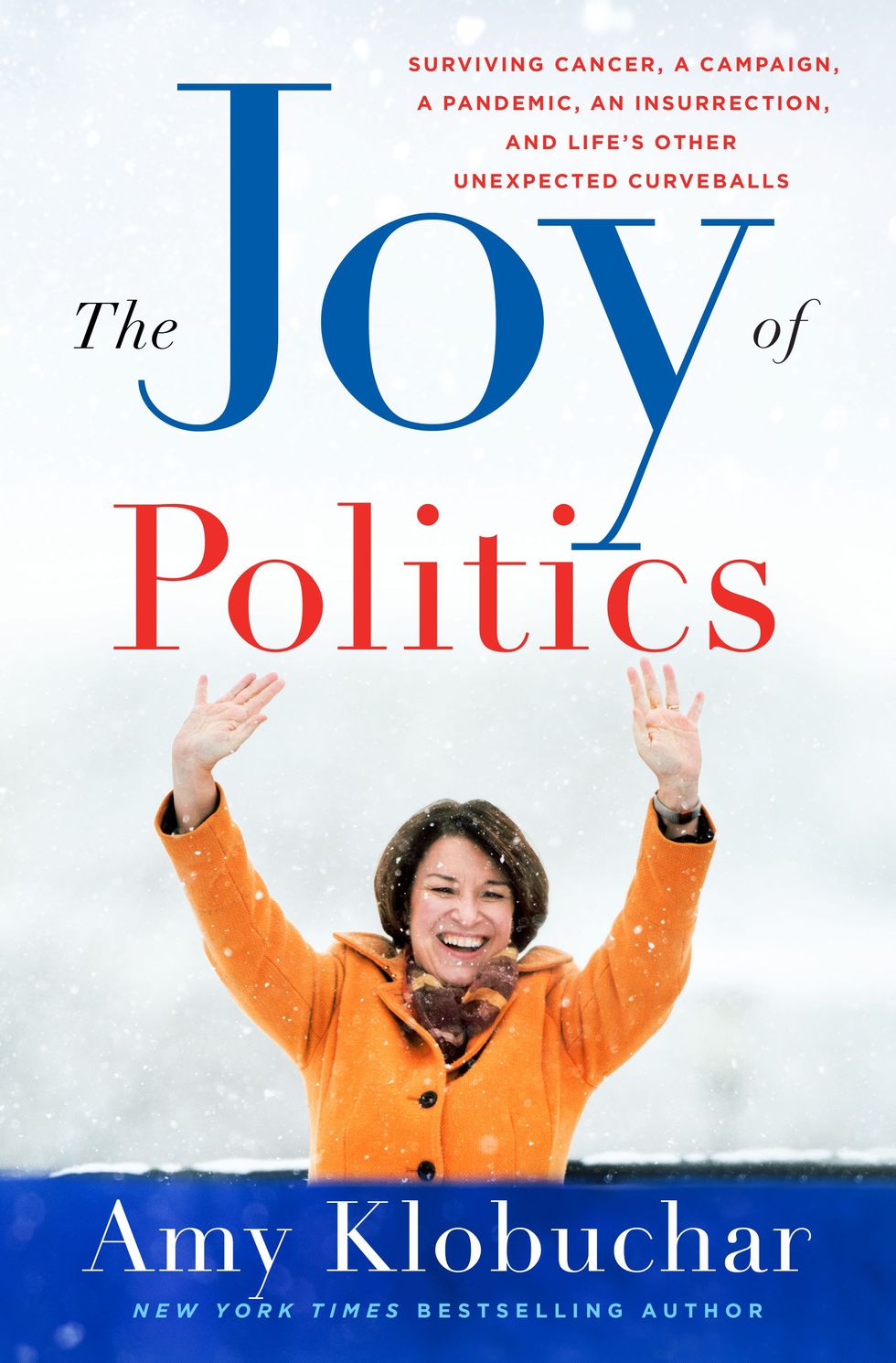

From The Joy Of Politics: Surviving Cancer, a Campaign, a Pandemic, an Insurrection, and Life’s Other Unexpected Curveballs by Amy Klobuchar. Copyright © 2023 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Amy Klobuchar, the daughter of a newspaperman and a schoolteacher, is the senior senator from Minnesota, the first woman from that state to be elected to the U.S. Senate. A national leader in the Democratic party, she ran for president in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary and has a well-earned reputation for working across the aisle to pass legislation that supports families, workers and businesses. She and her husband, John, have a daughter, Abigail.