Back in 1975, a collective of African American musicians, led by the visionary George Clinton, was staging ritualistic, retrofuturistic concerts in stadiums around the country. As Parliament-Funkadelic, the group espoused a cosmic mythology while playing music that was equal parts ancient and cutting-edge. The ultimate goal: black liberation.

Lauren Halsey wasn’t even born when all this went down, but the 32-year-old artist knows by heart the incantation that would sometimes accompany a flying saucer—aka “the Mothership”—landing onstage: “You have overcome, for I am here!” Halsey recites over the phone, while walking to the former beauty supply store and minimarket in South Central Los Angeles that she’s in the process of transforming into an art studio. “I saw the old marquee and signage, with ‘Beauty Supply’ painted underneath,” Halsey says of the nearly 6,000-square-foot building, “and I thought, ‘Oh wow, what a treat to take in all that energy.’ ”

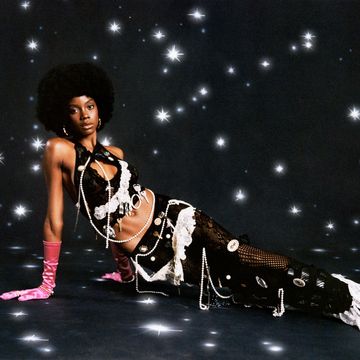

The South Central native draws from that same energy to build her own version of Motherships—brightly colored collages and installations that mix architecture with urban history, urban planning, and funk’s heavy lightness. Her sculptures and installations have landed everywhere from New York’s Center for Architecture to Paris’s Fondation Louis Vuitton. But each piece centers on South Central L.A., invoking her roots to summon the future.

More From ELLE

“My dad’s side of the family has been here since 1927,” Halsey says. “My mom’s side, since 1930-something. She’s been a teacher at the same school since before I was born, and my dad’s an accountant with a lot of neighborhood pride.” She laughs while recalling people’s reactions to finding out where she grew up. “They’re waiting to hear, you know, Boyz n the Hood,” she says. “And I’m like, ‘It was amazing! Glitter and playing tennis in the middle of the street and ice cream trucks and total freedom!’ ”

Listening to her parents’ P-Funk records was its own kind of salvation. “I just put on my headphones and went berserk! Just to have that space to experience myself differently, my most ideal self, without having to leave my bedroom. It was so extra, so dense. And then by 15 or 16, as I was getting into my queerness, I saw the queerness that was happening in the band. I started making these collages where I was, like, funkatizing the neighborhood and funkatizing the people. It changed me.”

During high school at the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, Halsey gathered these collages into a portfolio. Her aunt, a writer, introduced her to the artist Dominique Moody. “She had something special kind of nesting inside her,” Moody says. “She would embellish her sneakers with this incredibly intricate patterned imagery that had its own narrative and no symmetry.” Moody suggested she look into 3-D coursework, and Halsey wound up studying architecture at nearby El Camino College. She wasn’t so much interested in new construction as she was in “being able to think about how I can have a say in what’s built in my neighborhood.” And then figuring out how her neighbors could, too. Gentrification was on the horizon, and intertwined with the glitter and total freedom was evidence of struggle. “All the bars, all the bulletproof glass, all this armor around the buildings—that really fucks with your heart,” she says. “So I wanted to create these ‘interventions.’ ”

Halsey went on to earn a BFA at California Institute of the Arts in Valencia and an MFA at Yale University, then accepted an artist-in-residence position in 2014 at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Opening her studio window let in all that 125th Street had to offer: drumlines, parades, T-shirt vendors. “I formed relationships [with people] and brought them up to my studio,” she says. “I started thinking about hieroglyphs, and how they are a permanent record—how I could sample that to talk about people and assert our record into the canon, into history.” Amanda Hunt, now the director of education and senior curator of programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), was an associate curator at the Studio Museum when Halsey arrived. “I’ve been in various studios of Lauren’s over time, and what I’ve taken away is that it’s social,” Hunt says. “There’s always a collective community in there—music, conversation, and her in the corner with gesso on her hands.”

In 2018, Halsey was invited to participate in the biennial show Made in L.A. at the city’s Hammer Museum. Her piece, a mausoleum-like pavilion with some 600 engraved gypsum panels arranged in a grid, was titled The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture). Drawing upon both ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and contemporary street art, the panels incorporated black-owned business signage, barber illustrations, and images of victims of violence. That same year, Halsey went polychromatic and multimaterial in we still here, there, her solo show at MOCA. Housed within cool white grottoes constructed from white cement and mosaicked CDs was an eye-popping assortment of cultural ephemera: hair spray cans, durag packaging, action figures, party flyers. The work was politically engaged and queer—a proposition for what black DIY spaces could look like.

At the moment, Halsey is getting ready for a major solo show at David Kordansky’s cavernous L.A. gallery. The gallerist had been familiar with Halsey’s art practice for some time, “but seeing her installations at the Hammer and MOCA simultaneously [in 2018] was a revelation,” he says. “Her work felt fresh and ambitious yet rooted, poignantly, in L.A. and in our moment. It had been a while since I’d been so moved by the work of a young artist.”

Halsey’s also working on a major brand collaboration that’s set to launch in the near future (she can’t divulge with whom just yet) and dipping her toes in the architecture of virtual reality. “Someone approached me about it, and I was like, ‘What?’ But I went and tried it, and my mind was blown,” she says. She’s looking forward to researching and learning the programs to create virtual worlds. “Imagine neon and fantasy geographies and all eras of funk—POC paradises that you can experience,” she says. But grounded, as always, in a South Central state of mind. Halsey’s back at her studio now, which is around the corner from her mom’s place, a stone’s throw from the store she’s bought lunch from since middle school: “It’s just another extension of who and what we always were.”

Jesse Dorris is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn.