It is 3 A.M., and I am sitting on the floor of Erbil International Airport, stunned. Just a few days before, I had been waiting for my boyfriend, Salem, to come home from a reporting trip in Iraq. We had been living in Istanbul, Turkey for a little over a year and while neither of us are Turkish, it was the perfect place for us, two journalists, to live while covering stories across the Middle East.

Even though we came from different parts of the world—me, from the United States, and Salem, from Syria—this never felt like an insurmountable distance. We fell in love while covering the war in Syria and Turkish politics, bonded by our interest in the world around us. Now, he was on assignment in Iraq to report on the fall of the Islamic State, and I was eager for him to come home, safely.

Just as I was deciding what I was going to make for dinner in our apartment in Istanbul, he called me. “I’m being banned from Turkey,” he said, without so much as a greeting. It was my worst nightmare—even though we knew journalists who had been kicked out of the country, Salem was different. He was technically a refugee, and while most of our friends in Turkey could easily just “go home” if they ran into a problem, Salem could not return to Syria. He also was barred from traveling to most countries outside of the Middle East without a visa. And these visas—to places like Europe, Canada and the United States—were so impossible to obtain that many of our Syrian friends had boarded makeshift boats across the Mediterranean, in hopes of seeking asylum in Europe.

I flew to Iraq almost immediately after getting Salem’s call—and while we had spent a wonderful week together trying to pretend that everything was normal, it was now time for me to go home—without him. I didn’t know what I was going to do next. I didn’t want to leave the life that we had built in Istanbul behind. But I didn’t want to be in Turkey without him, either.

Most people do not have a U.S. passport, I thought, looking down at my own. It allowed me so much freedom of movement, that it felt unfair. As a journalist, I had been following the stories of refugees fleeing wars in the Middle East but had never considered how many love stories were cut short amidst the chaos. We are told that love conquers all. But what happens when you don’t have the right passport?

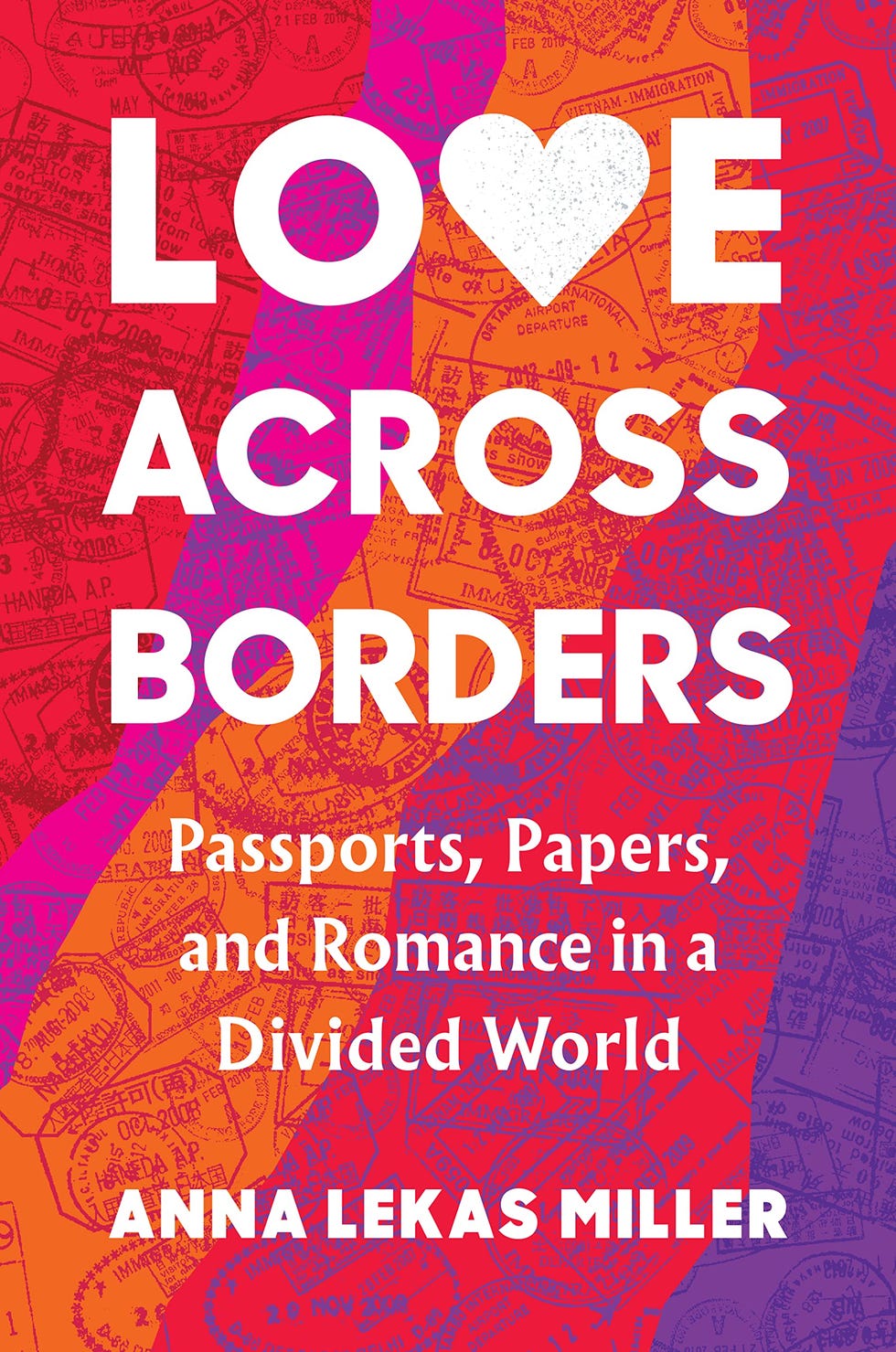

“I always tell my daughter—make sure he has papers before you fall in love,” Cecilia Garcia, a 48-year-old mother of five told me, when I met her in Chicago in July 2021. A few years had passed since I was sitting on the floor of the Erbil airport, and my journey with Salem had brought us to two different countries: first to Iraq, where we lived for nine months after he was deported from Turkey, and later, to the United Kingdom, where we now live because he was able to get political asylum. Inspired by our story, I had started writing a book, Love Across Borders, to chronicle the stories of how passports, papers and borders affect couples around the world.

Cecilia, who was born and raised in Chicago, knows firsthand how it feels to have your love story threatened by borders. Almost 10 years ago, her partner Hugo, was pulled over near their home in Chicago for an expired registration and deported to Mexico, thousands of miles away from her and their five children. Anyone deported from the U.S. is banned from reentering the country for a decade, leaving families like hers separated. While there are no official numbers of how many families are impacted by this Clinton-era policy, the group American Families United estimates that as many as 20,000 people are denied visas to join a U.S. citizen spouse every year.

“I feel so blessed to be able to visit him,” she told me, explaining that while, as a U.S. citizen, she can travel back and forth to Mexico, many of the people that she knows in a similar position are undocumented and cannot. Still, her desire to raise their children in the U.S. means she cannot uproot her life and relocate to Mexico, the way that I was able to move to Iraq. “I love my husband, and I love my kids, and I will always fight for them,” she tells me. “I always tell people, no border will get in the way of your love.”

Spending time with Cecilia made me realize how many women are essentially made single mothers because their partners are deported and how many children are rendered parentless when their non-citizen parents are deported. As a woman of a certain age, I am constantly fielding questions as to whether I am planning to have children. I never know how to answer; intentionally bringing life into a relationship where I have had to suddenly pack an apartment and move to a new country not once, but twice, feels unwise. We have watched countries—including the places where we first fell in love—fall apart, displacing friends and family time and again.

I’m not alone. “I know what it is like to have parents who are undocumented, and don’t think that I want to have children,” Karina Ambartsoumian-Clough, the executive director of United Stateless, tells me from her home in Philadelphia. Even though Karina’s family fled ethnic persecution in the former Soviet Union when she was a child, their request for asylum in the United States was denied. When they tried to go back, they were told that the country that was listed on their documents no longer existed; not only were they undocumented—they were stateless.

Even falling in love with, and marrying, a U.S. citizen—her husband, Kevin—didn’t help Karina fix her status. As a stateless person, the option to “marry someone for a green card” doesn’t apply. “It affects you, and it affects your marriage,” she said. “For a long time, I was depressed, and I brought that into our home. I was so ashamed about my status, and I let that control me. But I just don’t care anymore. I care about Kevin, and I care about our marriage and I care about the United Stateless community.”

Immigration can also force a more traditional way than modern couples may prefer. “I’m a millennial—I don’t want to get married!” Maria Lopez, a 29-year-old content creator who makes satirical memes about the struggles of dating while undocumented, told me. “But I feel like these immigration systems are forcing me.” I laughed in recognition. Spending time with Maria reminded me of all the times I’d rolled my eyes because someone said they didn’t believe in the “institution” of marriage. I didn’t believe in the “institution” of anything, but I had fallen in love with someone whose passport wasn’t worth the paper that it was printed on and the only way to enjoy equal rights—most crucially, the right to be together in the same country—was to become legally bound to one another. For me, marriage became the most romantic act in the world.

As I prepare to share our journey with the world in Love Across Borders—the good, the bad, and my ugliest, most unflattering moments—I remember how I used to long for what I thought was a “normal” relationship. I wanted to travel to romantic destinations together and seethed with jealousy at pictures of couples in places like Tuscany and Santorini—places Salem and I could not go. Looking back, I realize now that it was not so much that I wanted an enviable Instagram feed, it was that I wanted my partner to be able to travel as freely as I could—to experience the magic of a world without limits.

We have yet to visit Italy or Greece together, but we have watched countless sunsets over the Bosphorus and documented history unfolding across the Middle East. We have built a home together in London that is all the more meaningful because of what we have gone through together. Navigating borders and immigration systems in multiple countries meant that we had to prioritize one another and let go of what we sacrificed to be together. I travelled less than I wanted to; Salem put himself through the excruciating asylum process so that we could have a future together in a safe and stable country. No matter where we are, we learned that the most important thing is that we are together.

Anna Lekas Miller is a writer and journalist who covers the ways that conflict and migration shape the lives of people around the world. She has reported from Palestine, Lebanon, Turkey, and Iraq, and her work has appeared in Vanity Fair, The Intercept, New Lines Magazine, CNN, and many other outlets. She lives in London with her partner, Syrian journalist Salem Rizk.