Before Geena Rocero took the stage in front of hundreds of onlookers at May’s Summit at Sea, a multidisciplinary symposium aboard a cruise ship, she landed in Florida. It was an unsettling feeling for this model and leading transgender activist. After all, to be transgender in Florida today is to be “erased,” as Rocero says, referring to a recently signed Florida law that bans gender-affirming healthcare to minors.

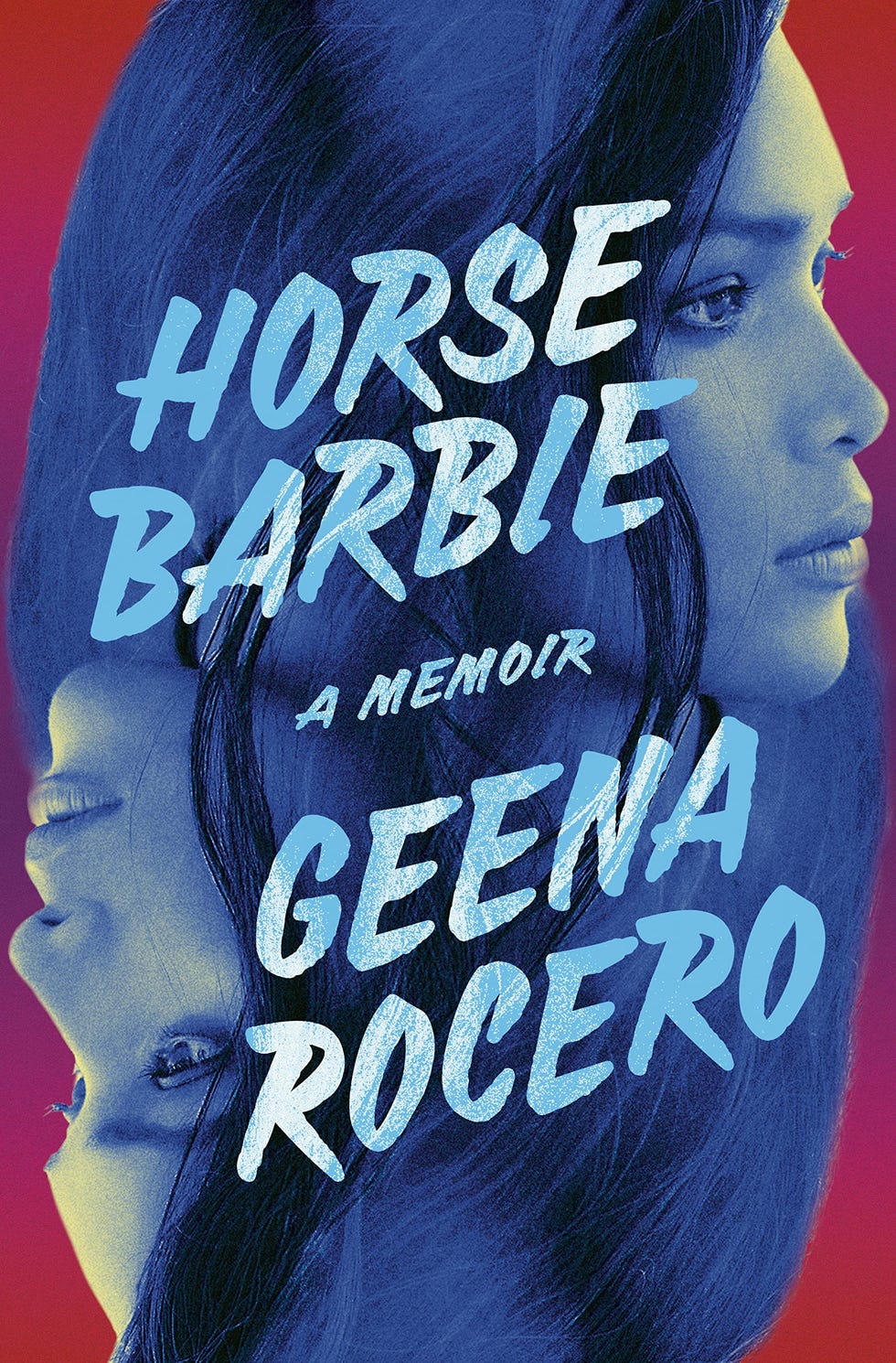

But that didn’t stop her from arriving in Florida and boarding the ship at the Port of Miami, ahead of the release of her memoir, Horse Barbie. In fact, it fueled her. “To place my body in a state that quite literally wants to erase me in all of my existence, it’s the most powerful way to resist and affirm myself,” Rocero says. “It’s a little ironic, but I considered it an honor to launch the cruise from Florida and tell my story to a space full of thought leaders.”

It’s the latest obstacle in a lifetime’s worth of indignation that Rocero has overcome as a transgender woman, which she recalls in 25 heartfelt chapters in Horse Barbie. The memoir’s pages are filled with stories of her journey from living as a femme boy in Catholic-heavy Philippines to winning a trans beauty pageant at age 15, to immigrating to the United States with a female gender marker on her documents, to becoming a highly sought model in New York City who appeared on magazine covers and in a John Legend music video. Rocero also captures another significant detail: the immense fear she felt in keeping her trans history a secret in the cutthroat fashion industry.

More From ELLE

For eight years, Rocero kept her story hidden from industry professionals—until she couldn’t take it anymore. In 2014, on perhaps one of the world’s biggest stages, she came out during a TED Talk, the clip of which has nearly 3.7 million views. Since then, Rocero has spoken at the White House in front of President Barack Obama and found new careers as an Emmy-nominated director and producer.

Rocero spoke with ELLE.com over the phone about what it meant to have a totally accepting family, including her hypermasculine father; her intense fear of being outed; and how Horse Barbie can serve as an anthem cry for trans youth.

Who did you write this book for?

I’d like to think that I’m writing to a person who is searching for something, especially when you’re at the tip of that quest, or questioning stories or expectations from our society. Whether it’s someone who comes from a religious background or has family that doesn’t accept them, or someone who is questioning themselves and asking what they wanted to do in their inner lives. They don’t have the same story as me—mine is a very singular journey—yet they are finding their own authentic self.

But really, deep down, I think I wrote this book for a specific person: a young trans Filipina girl who is part of the global diaspora. If you don’t feel connected and don’t see your own humanity, I hope you find some semblance of affirmation and self-value in the pages of this memoir.

Your story has touched so many lives since you came out publicly as transgender in 2014. Why was it important to also share it in memoir form?

When I decided to write this book, my general thought process around it was that yes, my story has been in the public consciousness, from the TED Talk, through my work with the Gender Proud advocacy group, meetings at the White House and with President Barack Obama. Yet, I knew I wanted to honor the artist in me and share the fullness of my life story. I wanted to share these bigger questions that I was asking myself when I was pursuing my own truth, questions about who I was—not just related to gender, but as a human being. This book was my opportunity to speak about my authentic self.

Today, 19 states are banning gender-affirming care for minors. How can this book be of value to them and their allies?

I wrote this book during the pandemic, but I knew since 2015 that I wanted to write a book. Coincidentally, we’re currently seeing an increase in attacks on trans youth, on Asians and others. In this memoir, I shared unapologetically the fullness of who I am, the fullness of what drives me, what feeds my curiosity—finding love, getting a career, being playful. I think this should always be seen as that. We should always live full lives. How others are trying to erase our identity, my response is: Look at this Horse Barbie, the story of a life that is full. If there’s a person who does still not understand the transgender community, who does not have interaction or an adjacent community to the trans community, this book is a way for them to understand.

You’ve mentioned the lengths you went through to hide your transgender identity in the modeling industry—carrying tampons to throw off the scent, hiding your neck and Adam’s apple. How scary was the idea of being outed?

I stand on the shoulders of so many past trans models who paved the way for me. Caroline Cossey—she’s one of the most visible trans women models in the 1970s—she gave me a sense of possibility and also a sense of caution. I wanted to be like her. But her story was taken from her, and she was outed in a British tabloid. Our community is littered with stories of trans women fashion models, and the moment they were outed, their careers were destroyed.

This book is to honor them. I was living in New York City during a time when I had to conceal much of my personal life. Thank God I got through it and was able to take control in some way of my narrative because so many people weren’t able to.

Let’s talk about the book title, Horse Barbie. You’ve turned around a once-mocking name from rival pageant contestants into a personal badge of honor. Today, what does “Horse Barbie” mean to you?

When I was beginning to write the book, the main topics were trans pageants and Catholicism—you can’t be more cinematic than that! As I described it, “Horse Barbie” first was a reclamation of an insult, when other contestants would tease me about my long neck and thick lips, and it was also a formation of a spirit. When my trans pageant mother, Tigerlily, saw me on stage, in my elegant dress, she said, “You actually look like a Horse Barbie,” this mythical essence and spirit. When I was in New York City, when it was really, really, really, really, really rough, I had to remind myself that’s who I was. At least in my mind, that spirit is in my mind and in my heart.

When I did my TED Talk in 2014, Horse Barbie came back. It was my first time giving a speech—I think we can say that this girl likes a big stage! And then, while on that stage, I became Horse Barbie.

Much like you, Filipino history is multi-layered: It’s a deeply Catholic nation, but it also celebrates transgender pageants and has been labeled as a “gay-friendly country.” What lessons in Filipino culture and its view of transgender people remain with you?

It’s important to understand the history of the Philippines. In pre-colonial times, there were babaylans, highly respected mystical healers who were mostly females or feminized males who had relations with other males. Our language, Tagalog, doesn’t even have gender pronouns like “he” or “she.” It wasn’t until Spanish colonization that the idea of heterosexual marriage roles were considered a norm.

But today, it’s about decolonizing my mind. It’s like my ancestors telling me this is how it should always be: no hard and fast rules about gender. That’s one reason we have transgender pageants, because of the resilience of the culture that we have to stay true to our roots.

One of my favorite passages in your book is a moment between you and your father, as you walk into your high school together: “‘There is nothing wrong with you,’ he said. ‘Chin up, anak.’ And with that he nudged me back toward the classroom, his touch as gentle as his heart as he guided us down the hall.” What do you think your father, who passed away in 2001, would say about you today, about his “bojojoy”?

Ah, you’re going to make me cry. … I hope he knows how much of a role he played in me having an early understanding of having access to freedom at such a young age and be free to be who I am. When I was writing this book, I had to ask my sisters if there was ever a time that Papa was upset at me for being who I am. We asked ourselves if it really did or didn’t happen, if he really ever was accepting of me. Not one of us could recall a time when he was upset at having a femme boy. He really accepted me.

This book is truly the first time I can honor that role of his. The normally macho and very Catholic and easy-to-anger man did not express those sides at his femme boy. Not once did he question who I am. I tried my best to explain it in the book, about how he felt demoralized at not being the breadwinner of the house, how he wished he could be allowed to express his deeper emotions, how he let his hypermasculinity out but wished his gentleness was more apparent. The way he saw me swaying in my skirt, I like to think that he recognized something in himself.

It must have been affirming to have a supportive family and community. For the rest of us, how can we better support our trans friends, families, and neighbors in their journey to be visible and affirmed?

I lived half of my life in the Philippines, half in the U.S., so I’ve seen how different worlds treat and view trans people. Culturally speaking, the U.S. and the Philippines are so different. In the Philippines, we have a word—kapwa—it’s a virtue, an ethos. It’s about how your inner self is a reflection of your community; it gives the idea that you don’t exist as an individual, that you are buttressed by those around you. So it was a shock when I moved to the U.S. and discovered we are by ourselves and alone in many respects.

In the TED Talk in 2014, I brought trans lives into public consciousness and have carried that on through advocacy. For so long, at least in the American context, being trans is about being visible. But I’ve learned that it’s not the one true answer, though. Taking that experience, taking the grounding of that culture I was raised in, it’s about community, the one part of who you are. Being there for one another is so important. In fact, it’s possibly the most important thing we can do.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Makeup by Ryanne Cleggett; hair by Gani Millama.

Nila Do Simon is a lifestyle and culture writer whose pieces have appeared in Condé Nast Traveler, Vogue.com, Garden & Gun, Marie Claire, and The New York Times. The runt in her family, she’s developed an interest in highlighting the voices of marginalized individuals and groups who, like her, can use an extra-loud microphone to be heard over the crowd.